February 14, 2005

Dear

friends,

I started to write

this when I was honored to be one of the play therapists selected by the

Association

for Play Therapy and OperationUSA to

go to Sri Lanka after the Tsunami to play with children. It was one of

the

most amazing experiences of my life, and I want to thank you for all

the support

you gave me. I continued to write in Sri Lanka, and then, back home,

fueled by jet lag (which I think was really 'soul lag') I kept writing.

And writing. And I may have written too much, so feel free to skip around,

or just look at the pictures.

This is my thank

you to all of you for your support and donations, for the stickers,

band-aids and crayons, for the drawings the children did here, for the

children in Sri Lanka; and to the amazing teams I worked with (from APT:

Janine,

David, Joe, Prabha, Jodi,

Sharolyn,

Valerie,

Maria;

from

OpUSA: Nimmi, Carinne, Ravi and

Anita) and my gratitude to the incredible "animators" of Sri

Lanka, who taught me so much; and to Reverend J. and Selvie-Amah, and

all the children at St. John's orphanage. Most certainly and most especially

my

eternal gratitude to all the wonderful children

and adults

of Sri Lanka who, having survived the war and the Tsunami, opened their

hearts to me.

Thank you forever,

Kate

Kate Amatruda

Tsunami

A

visit to Sri Lanka

A humanitarian mission sponsored

by the Association for Play Therapy and OperationUSA

by

Kate

Amatruda, LMFT, CST-T, BCETS

|

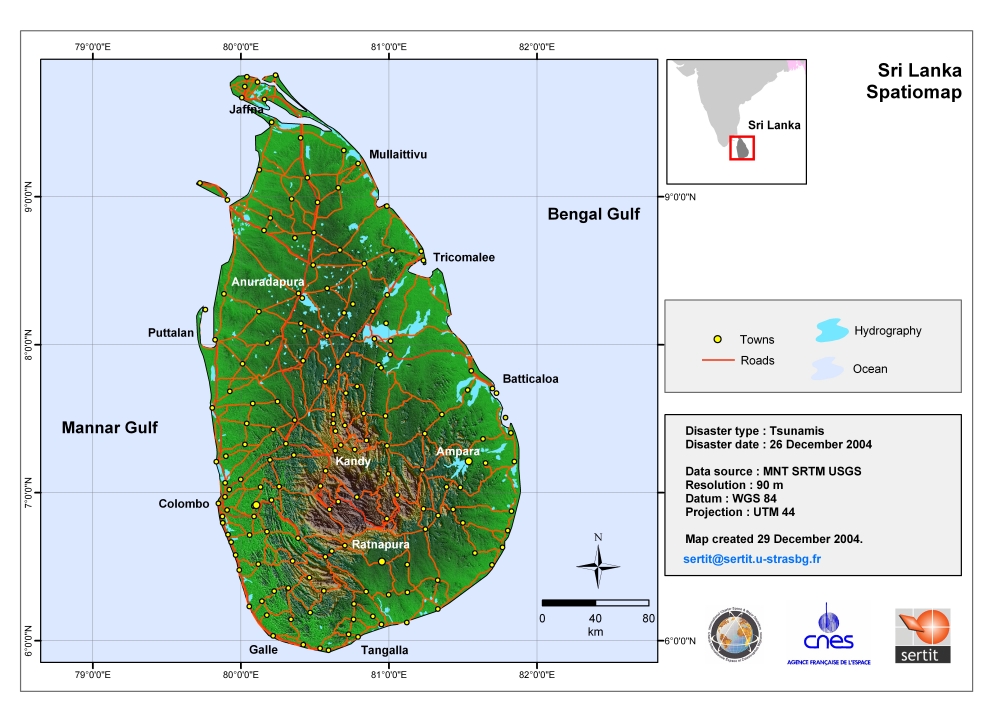

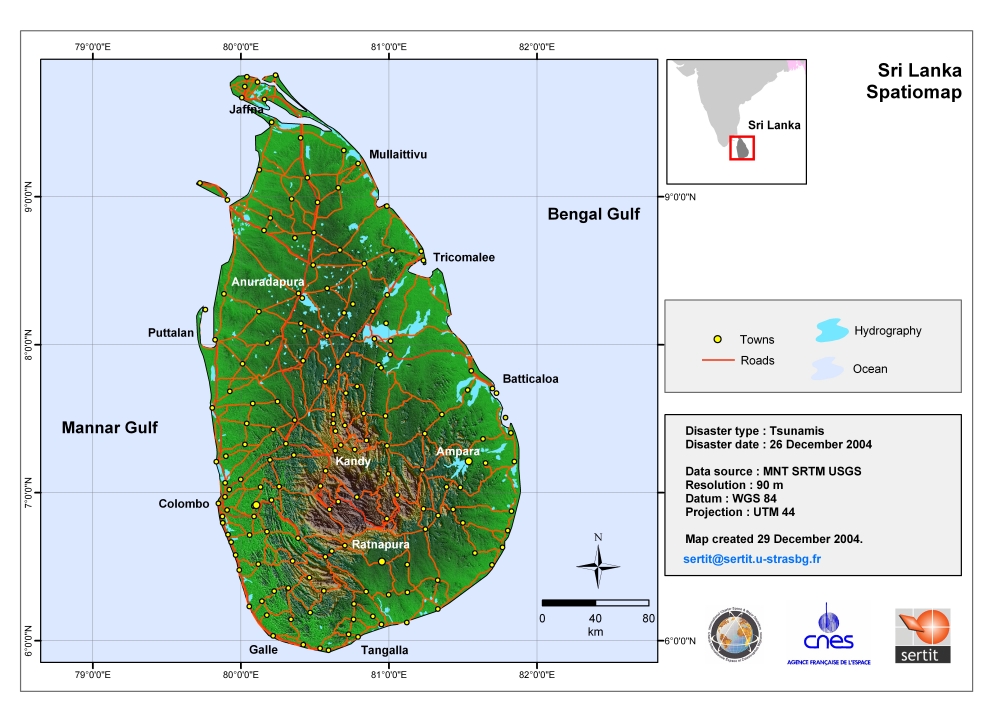

I look on the map and see that Sri Lanka is a teardrop off the coast of India.

I have not slept through the night since I returned from Sri Lanka five

days ago.

It

is

the eyes that haunt me; the eyes of the father whose daughter was ripped out

of his

arms,

the

eyes

of

the

grandmother who saw her children and grandchildren swept away. A generation lost

in a heartbeat. I see shock on the faces of the survivors, and am

reminded

yet again of how everything can change in an instant. Whether it

is an earthquake, a Tsunami, a tornado, or planes hitting towers, life

is so fragile. Everything can be gone in the blink of an eye; we

are so little, nature and war are so big. Yet we have this illusion, at least

in

the

West, that we are in control. So I look, and look again, compelled

to try to discern how people do it. How do you go on when your village,

your home, your family, is destroyed? I see the faces of those who

I met in the refugee camps, and it is the eyes that capture me. And

it

is

the eyes of the children that haunt me, and make me unable to sleep through

the night.

The

number of people believed killed in December's Tsunami disaster rose to 285,993

on Saturday, February 12, 2005. Every day the death toll rises. The number

of children orphaned is still unknown. Sri Lanka's death toll now stands

at 43,832. (Reuters)

The earthquake hit on Sunday, December 26, 2004 at 7:58:53 AM = local time at

epicenter

For us in California, it was on Christmas afternoon,

Saturday, December

25, 2004 at 04:58:53 PM (PST)

Location 3.307° N 95.947° E

Depth 30 km (18.6 miles) set by location program

Region OFF THE WEST COAST OF NORTHERN SUMATRA.

It was a 9.0 earthquake, the fourth biggest since 1900.

(This

should be animated to show the Tsunami. If it is not, try passing your mouse

over the map.

If it does not animate, the non-animated map below shows the

course of the Tsunami.)

I am remembering

the Northern California Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989. The

Indian

Rim "Boxing Day" 9.0 earthquake

makes our 6.9 magnitude pale in comparison,

as

each Richter logarithmically increases the size on an earthquake,

yet the Loma Prieta was strong enough to break the Bay Bridge. Scientists

from Pasadena explain,

"It

has

since

been

shown

to

be proportional to the energy released in the earthquake but the energy

goes up with magnitude faster than

the

ground velocity, by a factor of 32. Thus, a magnitude

6 earthquake has 32 times more energy than a magnitude 5 and almost 1,000

times

more energy than a magnitude 4 earthquake."

"The massive earthquake off the west coast of Indonesia on December

26, 2004, registered a magnitude of nine on the new "moment" scale

(modified Richter scale) that indicates the size of earthquakes.

It was the fourth largest earthquake in one hundred years and largest

since the 1964 Prince William Sound, Alaska earthquake.

The devastating mega thrust earthquake occurred as a result of

the India and Burma plates coming together. It was caused by the

release

of stresses that developed as the India plate slid beneath the

overriding Burma plate. The fault dislocation, or earthquake, consisted

of a

downward sliding of one plate relative to the overlying plate.

The net effect

was a slightly more compact Earth. The India plate began its descent

into the mantle at the Sunda trench that lies west of the earthquake's

epicenter.

For information and images on the Web, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/vision/earth/lookingatearth/indonesia_quake.html

For the details on the Sumatra, Indonesia Earthquake, visit the

USGS Internet site:

http://neic.usgs.gov/neis/bulletin/neic_slav_ts.html

http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2005/jan/HQ_05011_earthquake.html

Question: How much energy was released by this earthquake?

Answer: Es 20X10^17 Joules, or 475,000 kilotons (475 megatons)

of TNT, or the equivalent of 23,000 Hiroshima bombs

.

When I get home, I read:

Sumatra Earthquake Three Times Larger Than Originally Thought

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Northwestern University seismologists

have determined that the Dec. 26 Sumatra earthquake that set off a deadly

Tsunami throughout the Indian Ocean was three times larger than originally

thought, making it the second largest earthquake ever instrumentally recorded

and explaining why the Tsunami was so destructive.

By analyzing seismograms from the earthquake, Seth Stein and Emile Okal,

both professors of geological sciences in Northwestern's Weinberg College

of Arts and Sciences, calculated that the earthquake's magnitude measured

9.3, not 9.0, and thus was three times larger. These results have implications

for why Sri Lanka suffered such a great impact and also indicate that the

chances of similar large tsumanis occurring in the same area are reduced.

"The rupture zone was much larger than previously thought," said Stein. "The

initial calculations that it was a 9.0 earthquake did not take into

account what we call slow slip, where the fault, delineated by aftershocks,

shifted

more slowly. The additional energy released by slow slip along the

1,200-kilometer long fault played a key role in generating the devastating

Tsunami.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/02/050211094339.htm

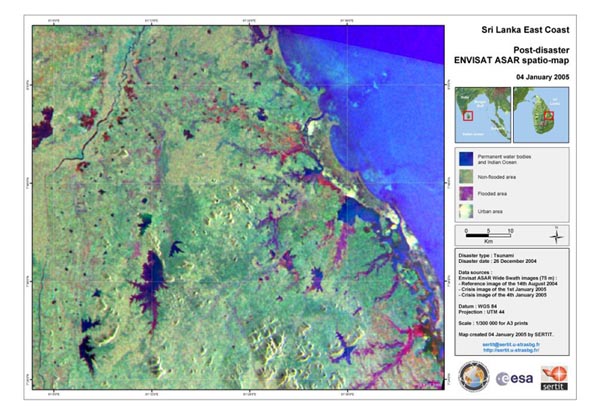

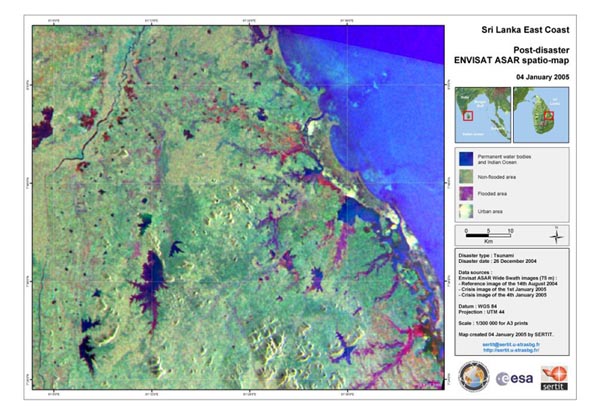

Satellite Imagery

This image acquired on 28 December 2004 by the MERIS (Medium Resolution Imaging

Spectrometer) on board ESA's Envisat Earth observation satellite shows

the northeast coast of Sri Lanka and the southern coasts of India. Sediment

(light

brown & green colour) left after the Tsunami can be seen along the

coast. (Credit: ESA)

Tsunamis

When

thrust-faulting earthquakes happen under the ocean, the earthquake

can push large blocks of ocean floor

up. When the ocean

floor moves up, the water that was in that spot

has to go somewhere else. That somewhere else is into a large wave

called a Tsunami.

http://pasadena.wr.usgs.gov/ABC/pt.html

I

keep feeling there is a "disturbance

on the field"; that something is very wrong.

NASA Details Earthquake Effects on the Earth

NASA scientists using data from the Indonesian earthquake calculated

it affected Earth's rotation, decreased the length of day, slightly

changed the planet's shape, and shifted the North Pole by centimeters.

The earthquake that created the huge Tsunami also changed the

Earth's rotation.

http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2005/jan/HQ_05011_earthquake.html

Children in the Bay Area of San Francisco, where I live, are

anxious about a Tsunami hitting here. The San Francisco Chronicle has an article

about it, so I am able to reassure my son, as well as myself, that we would

be in no danger. We live on the Petaluma River, but find out that we would

be

protected by the deep channel through the Golden Gate Bridge. Deep harbors

are more able to absorb the shock of a Tsunami than shallow waters.

I received

an e-mail from the Association for Play Therapy calling for a team of volunteers

"to participate in a US delegation to Sri Lanka to provide play activities

(but not psychotherapy) to children in orphanages and community

centers."

I quickly

faxed and mailed off my application, hoping to be selected. I was so honored

when when Dr. Janine Shelby, the Association for Play Therapy Foundation

President, and a brilliant clinician, called to invite me to join the project. I

learned later that only 14 play therapists from across the country have been

selected to go. We will be working with OperationUSA,

an NGO that was the co-recipient

of

the

1997

Nobel

Peace Prize for its work banning land mines. Their mission is based

upon Mahatma Gandhi's belief that "You

must be the change you wish to see in the world".

After

the initial elation, panic sets in. What am I going to do there? I don't

speak the language, nor know the culture. I madly research techniques

for working with children after a disaster, and find very little. There

is a need for Dr. Shelby's project, which will be to bring specific cognitive-behavioral

protocols, in the form of games, to the field.

I find

that the Save the Children guidelines are:

1.Apply

a long-term perspective that incorporates psychosocial well being of

children.

2.Adopt a community-based approach that encourages self-help

and builds on local culture, realities and perceptions

of child development.

3.Promote normal family and everyday life so as to reinforce

a child’s

natural resilience.

4.Focus on primary care and prevention of further

harm in the healing of children’s psychological

wounds.

5.Provide support as well as training for personnel who

care for children.

6.Ensure clarity on ethical issues in order to protect

children.

7.Advocate children’s rights.

I have

ten days notice in which to prepare. I have to tell my patients, and work

through their feelings about me going so soon after the holiday break.

One mother sums it up, "Well, while I am glad for all those children

that you will help, I am not happy for my daughter who you will be leaving!" Shots

- I rush to the doctor to get Hepatitis A and B vaccines, Typhoid, tetanus

and diphtheria shots, and malarial prophylactic pills. After the shots, I

cannot raise my arms for days. I have to pack; we are told to wear long sleeved

shirts (with high cut necklines) and pants. I go to Target and buy loose

fitting

cotton outfits in the pajama department. I will not be a fashion plate this

trip, that's for sure. I spent hundreds of dollars on over-the-counter stuff:

mosquito repellant, sunscreen, tea tree oil, antacids, anti-diarrhea pills,

Advil, Tylenol, anti-itch cream and pills, wipes, toilet paper, hand sanitizer,

etc. I feel like a walking pharmacy.

My

sister, Elizabeth Howell, tells me that one her colleagues and dearest friends

at Calvin College, where they both teach, is from Sri Lanka. His name is

Kumar

Sinniah; he is an Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry.

He is wonderful, e-mailing me information, and offering to hook me up with

his five sisters in Sri Lanka. I get helpful e-mails from his sisters Sharmini,

who is working with the Christian Blind Mission, and Melanie.

My one regret was that I was unable to call with them or meet

them when I was in Sri Lanka. When I had a few minutes, finally, on our

last day in Colombo, my laptop, with their phone numbers, went on a little

jaunt through Colombo on its own. Fortunately, it returned intact and in

time for the plane.

To

further prepare, especially emotionally, I go to the Center for Disease Control,

the National Center for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and the National

Center for Child Traumatic Stress. (The following articles are in the public

domain. Feel free to skip them if you just want to read about my journey.)

Disaster Rescue and Response Workers

A National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet

The terrorist attacks on New York and Washington are, together, the greatest

man-made disaster in America since the Civil War. Lessons learned from

natural and human-caused disasters can help us understand the unique stressors

faced by rescue workers such as police and firefighters, National Guard

members, emergency medical technicians, and volunteers. Past experience

may also help us recognize how these stressors may affect response

workers. Rescue workers face the danger of death or physical injury, the

potential loss of their coworkers and friends, and devastating effects

on their communities. In addition to physical danger, rescue workers are

at risk for behavioral and emotional readjustment problems.

What psychological problems can result from disaster experiences?

The psychological problems that may result from disaster experiences include:

- Emotional reactions: temporary (i.e., for several days or a couple

of weeks) feelings of shock, fear, grief, anger, resentment, guilt, shame,

helplessness, hopelessness, or emotional numbness (difficulty feeling

love and intimacy or difficulty taking interest and pleasure in day-to-day

activities)

- Cognitive reactions: confusion, disorientation, indecisiveness, worry,

shortened attention span, difficulty concentrating, memory loss, unwanted

memories, self-blame

- Physical reactions: tension, fatigue, edginess, difficulty sleeping,

bodily aches or pain, startling easily, racing heartbeat, nausea, change

in appetite, change in sex drive

- Interpersonal reactions in relationships at school, work, in friendships,

in marriage, or as a parent: distrust; irritability; conflict; withdrawal;

isolation; feeling rejected or abandoned; being distant, judgmental,

or over-controlling

What severe stress symptoms can result from disasters?

Most disaster rescue workers only experience mild, normal stress reactions,

and disaster experiences may even promote personal growth and strengthen

relationships. However, as many as one out of every three rescue workers

experience some or all of the following severe stress symptoms, which may

lead to lasting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders,

or depression:

- Dissociation

(feeling completely unreal or outside yourself, like in a dream; having "blank" periods

of time you cannot remember)

- Intrusive reexperiencing (terrifying memories, nightmares, or flashbacks)

- Extreme attempts to avoid disturbing memories (such as through substance

use)

- Extreme emotional numbing (completely unable to feel emotion, as if

empty)

- Hyper-arousal (panic attacks, rage, extreme irritability, intense agitation)

- Severe anxiety (paralyzing worry, extreme helplessness, compulsions

or obsessions)

- Severe depression (complete loss of hope, self-worth, motivation, or

purpose in life)

Who is at greatest risk for severe stress symptoms?

Rescue workers who directly experience or witness any of the following

during or after the disaster are at greatest risk for severe stress symptoms

and lasting readjustment problems:

- Life threatening danger or physical harm (especially to children)

- Exposure to gruesome death, bodily injury, or dead or maimed bodies

- Extreme environmental or human violence or destruction

- Loss of home, valued possessions, neighborhood, or community

- Loss of communication with or support from close relations

- Intense emotional demands (such as searching for possibly dying survivors

or interacting with bereaved family members)

- Extreme fatigue, weather exposure, hunger, or sleep deprivation

- Extended exposure to danger, loss, emotional/physical strain

- Exposure to toxic contamination (such as gas or fumes, chemicals, radioactivity)

Studies also show that some individuals are at a higher than typical risk

for severe stress symptoms and lasting PTSD if they have a history of:

- Exposure to other traumas (such as severe accidents, abuse, assault,

combat, rescue work)

- Chronic medical illness or psychological disorders

- Chronic poverty, homelessness, unemployment, or discrimination

- Recent or subsequent major life stressors or emotional strain (such

as single parenting)

Disaster stress may revive memories of prior trauma and may intensify

preexisting social, economic, spiritual, psychological, or medical problems.

How can you manage stress during a disaster operation?

Here are some ways to manage stress during a disaster operation:

Develop a "buddy" system

with a coworker.

Encourage and support your coworkers.

Take care of yourself physically by exercising regularly and eating small

quantities of food frequently.

Take a break when you feel your stamina, coordination, or tolerance for

irritation diminishing.

Stay in touch with family and friends.

Defuse briefly whenever you experience troubling incidents and after each

work shift.

How can you manage stress after the disaster?

After the disaster:

- Attend a debriefing if one is offered, or try to get one organized

2 to 5 days after leaving the scene.

- Talk about feelings as they arise, and be a good listener to your coworkers.

- Don't take anger too personally - it's often an expression of frustration,

guilt, or worry.

- Give your coworkers recognition and appreciation for a job well done.

- Eat well and try to get adequate sleep in the days following the event.

- Maintain

as normal a routine as possible, but take several days to "decompress" gradually.

How can you manage stress after returning home?

After returning home:

- Catch up on your rest (this may take several days).

- Slow down - get back to a normal pace in your daily life.

- Understand that it's perfectly normal to want to talk about the disaster

and equally normal not to want to talk about it; but remember that those

who haven't been through it might not be interested in hearing all about

it -they might find it frightening or simply be satisfied that you returned

safely.

- Expect disappointment, frustration, and conflict -sometimes coming

home doesn't live up to what you imagined it would be -but keep recalling

what's really important in your life and relationships so that small

stressors don't lead to major conflicts.

- Don't be surprised if you experience mood swings; they will diminish

with time.

- Don't overwhelm children with your experiences; be sure to talk about

what happened in their lives while you were gone.

- If talking doesn't feel natural, other forms of expression or stress

relief such as journal writing, hobbies, and exercise are recommended.

Taking each day one at a time is essential in disaster's wake. Each day

provides a new opportunity to FILL-UP:

* Focus Inwardly on what's most important to you and your

family today;

* Look and Listen to learn what you and your significant

others are experiencing, so you'll remember what is important and let go

of what's not;

* Understand Personally what these experiences mean to you,

so that you will feel able to go on with your life and even grow personally.

______________________________________________________________________________

Psychological Impact of the Tsunami Across the Indian Rim

National Child

Traumatic Stress Network

www.NCTSNet.org

The massively

destructive Tsunami that struck across the Indian Rim caused

extensive loss of life and injury as well as devastation to property

and community

resources. The combination of life-threatening personal experiences,

loss of loved ones and property, massive disruption of routines and

expectations

of daily life, pervasive post-disaster adversities, and enormous

economic impact on families and entire nations pose an extreme psychological

challenge

to the recovery of children and families in the affected areas.

This brief information sheet provides an overview of expected psychological

and physical

responses among survivors. The key concepts include:

o

Reactions to Danger

o

Posttraumatic Stress Reactions

o Grief Reactions o Traumatic Grief o

Depression

o Physical Symptoms o Trauma and Loss Reminders

o Post-disaster

Adversity/Disruption

Appreciating

the psychological implications of such an overwhelming event on the lives

of the survivors plays a crucial role

in considering specific efforts that will be of greatest help to the

affected

communities. The following issues may be helpful to consider in efforts

to respond to disaster victims:

Reactions

to Danger

It

is important to recognize the difference between a sense of danger and

reactions to

traumatic

events. Danger refers to the sense that events or activities have

the potential to cause harm. In the wake of the recent disaster, people

and communities

have greater appreciation for the enormous danger of a Tsunami

and the need for an effective early warning system. There are likely

to

be

widespread

fears of recurrence that are increased by misinformation and rumors.

Danger always increases the need and desire to be close to others,

making separation

from family members and friends more difficult.

Posttraumatic

Stress Reactions

These

reactions are common, understandable, and expectable, but are nevertheless

serious and can lead to many difficulties in daily life. There

are three types of posttraumatic stress reactions. Intrusive Reactions

are ways

the traumatic experience comes back to mind.

These

include:

o

recurrent

upsetting

thoughts or images that occur while awake or dreaming

o

strong emotional or physical reactions to reminders of the Tsunami

o

feelings

and

behavior as if something as terrible as the Tsunami

is happening again

Avoidance

and Withdrawal Reactions include:

o

avoiding talking, thinking, or having feelings about the Tsunami

o avoiding

places and

people

connected to

the event

o feeling emotionally numb, detached

or estranged from others

o

losing interest in usually pleasurable activities

Physical Arousal Reactions are

physical changes that make the

body react as if danger is

still present.

These

include:

o

constantly being “on

the lookout” for danger

o being startled easily or being jumpy or

nervous

o feeling ongoing irritability or having outbursts of anger

o

having difficulty falling or staying asleep or having restless, easily

disturbed sleep

o having difficulty concentrating or paying attention

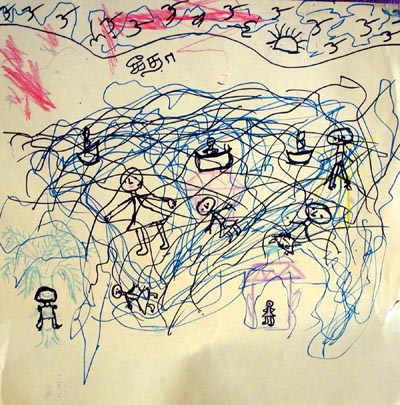

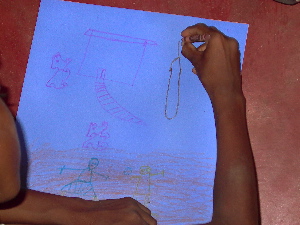

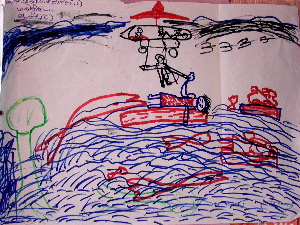

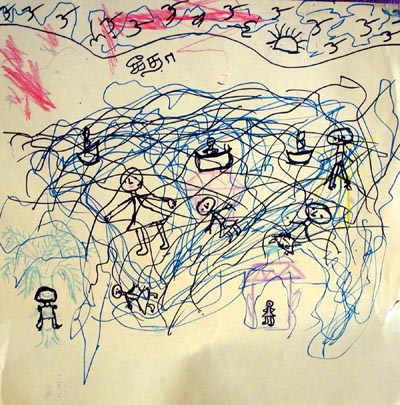

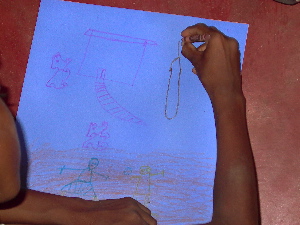

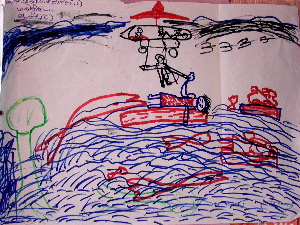

Children

may show some of these reactions through their play or drawing. They

may have bad dreams that are not specific to the Tsunami. In addition

to increased irritability,

children may also have physical complaints (headaches,

stomachaches, vague aches

and pains). Sometimes these are difficult to distinguish from true

medical concerns.

Grief

Reactions

Those

who survived the Tsunami have suffered many types of losses – including

loss of loved ones, home, possessions, and community. Loss may lead to:

o

feelings of sadness and anger

o guilt or regret over the loss

o missing

or longing

for the deceased

o

dreams of seeing the person again

These

grief reactions are normal, vary from person to person, and can last

for many years after

the loss. There is

no single “correct” course of grieving.

Personal, family, religious and cultural factors affect the course of grief.

Although grief reactions may be painful to experience, especially at first,

they are healthy reactions and reflect the ongoing significance of the

loss. Over time, grief reactions tend to include more pleasant thoughts

and activities, such as positive reminiscing or finding positive ways to

memorialize or remember a loved one. One of the many untoward results of

the Tsunami is that some family members’ bodies

have not been found. This,

unfortunately, has prevented

the normal use of religious,

and cultural

burial and mourning rituals,

and has put

the experience of grief

on hold. Whereas trauma

is more restricted to

personal experience of

the Tsunami, loss and grief

extend well beyond the

impacted

areas, indeed across the

world.

Traumatic

Grief

People

who have suffered the traumatic

loss of a loved

one often find grieving more difficult.

Their minds stay

on the circumstances

of the death,

including preoccupations

with how the loss could have been

prevented, what

the last moments

were like, and issues of accountability.

These reactions

include:

o intrusive, disturbing

images of the

manner of death that interfere with

positive remembering

and reminiscing

o delay in the onset of healthy

grief reactions

o retreat from close relationships

with

family and friends,

and avoidance of usual activities

because they

are reminders of the traumatic loss

Traumatic

grief changes

the course of mourning, putting

individuals

on a different time course than is usually

expected by

other family members, religious rituals,

and cultural

norms that offer support

and comfort.

Depression

Over

time, the risk of depression after the Tsunami is an additional

major concern. Depression is

associated

with prolonged grief and strongly related

to the

accumulation of post-Tsunami adversities.

Symptoms

include:

o persistent depressed or irritable

mood

o

loss of appetite

o sleep

disturbance,

often

early morning

awakening

o

greatly

diminished

interest

or pleasure

in

life

activities

o fatigue

or loss

of energy

o feelings

of worthlessness

or guilt

o feelings

of hopelessness,

and sometimes

thoughts

about

suicide

Demoralization is a common

response

to acutely

unfulfilled

expectations

about

improvement in

post-disaster

adversities,

and resignation

to adverse

changes

in life circumstances.

Physical

Symptoms Survivors

of

the Tsunami may experience

physical

symptoms,

even

in the absence

of

any underlying physical

injury

or illness.

These

symptoms include:

o

headaches, dizziness

o

stomachaches,

muscle

aches

o rapid

heart

beating

o

tightness

in

the chest

o

loss

of appetite

o bowel

problems

In

particular,

near-drowning

experiences

can

lead to panic

reactions,

especially

in

response to reminders.

Panic

often

is expressed

by

cardiac, respiratory,

and

other physical

symptoms.

More

general anxiety

reactions

are

also to

be

expected. Physical

symptoms

often

accompany posttraumatic

grief

and depressive

reactions.

More

generally, they

may

signal

elevated

levels

of life

stress.

Trauma

and Loss Reminders

Posttraumatic stress

reactions are

often evoked

by trauma reminders.

Many people

continue to encounter

places, people,

sights, sounds, smells, and

inner feelings that remind

them of the Tsunami experience.

The ocean

has become

a powerful

reminder. Additionally,

the tide simply

going out or

even the wave in

a bathtub

while bathing

a child can

act as a

disturbing reminder.

Because the Tsunami was

accompanied by

a loud

roar and

the crashing of waves,

loud noises can be

strong reminders.

Reminders can

happen unexpectedly, and it can

take quite a while

to calm down

afterward. Adults

and children are often

not aware that

they are responding

to a

reminder, and

the reason

for their

change in mood

or behavior may go

unrecognized. The day of

the week, the time

of day,

and the anniversary

date are common

reminders. Television

and radio news

coverage can

easily serve

as unwelcome reminders.

It is particularly difficult

when family

members have been

together during

a traumatic experience,

because afterward

they can serve

as trauma reminders

to each other, leading to

unrecognized disturbances

in family relationships.

Grief

reactions are often

evoked by loss

reminders. Those

who have lost

loved ones

continue to

encounter situations

and circumstances that

remind them of

the absence

of their loved

one. These reminders

can bring

on feelings

of sadness, emptiness

in the

survivor's life,

and missing

or longing for

the loved one's

presence.

There

are several types

of loss reminders: Empty

situations occur

when one would

be used to being with

a loved one

and they are no longer

there, for

example at the

dinner table,

during activities

usually done together,

and on special occasions,

like birthdays and holidays.

Children, adolescents,

and adults

also are

reminded by

the everyday changes

in their lives,

especially hardships

that result from

the loss.

Examples include

temporary or changed

caretakers, decreases

in family income,

depression and

grief reactions

in other family

members, disruptions

in family functioning,

increased family

responsibilities, lost

opportunities (for example,

sports, education, and

other activities),

and the loss of a sense

of protection

and security.

Post-disaster

Adversities/Disruption

Successfully

addressing the

multitude of post-disaster

adversities not

only saves lives,

protects health,

and restores

community function,

but constitutes an important

mental health intervention.

Contending with

adversities such as

lack of shelter,

food and other resources,

and disruption

of daily routines

can significantly deplete

coping and

emotional resources

and, in

turn, interfere with recovery

from posttraumatic

stress, traumatic

grief, and

depressive reactions.

Post-disaster medical

treatment and

ongoing physical rehabilitation

can

be another

source of

post-disaster stress.

New or

additional traumatic

experiences and

losses after

the initial

experience are

known to

exacerbate distress

and interfere

with recovery.

Likewise, distress

associated with

prior traumatic

experiences or

losses can

be renewed

by the

experience of

the Tsunami.

Children’s

recovery is put in jeopardy without proper caretaking, reunification

with family members, and restoration of normal daily routines – for

example, schooling. Some adversities require large-scale responses,

while others

can be addressed, in part, by personal and family problem solving.

What

Are the Consequences of These Reactions?

Post-disaster

reactions can be

extremely distressing and may significantly interfere with daily activities.

For adults, posttraumatic stress, grief, and depressive reactions

can impair effective decision-making, so vital in adapting to the recovery

environment.

They also compromise parenting. For children and adolescents, intrusive

images and reactivity to reminders can seriously interfere with learning

and school performance. Worries and fears may make it difficult for

young children to return to school or to venture any distance

from parents or

caregivers.

Avoidance

of reminders can lead adolescents to place restrictions

on important activities, relationships, interests and plans for the

future. Irritability can interfere with getting along with family

members and friends.

Trauma-related sleep disturbance is often overlooked, but can be especially

persistent and affect daytime functioning. Adolescents and adults

may respond to a sense of emotional numbness or estrangement by using

alcohol or drugs.

They may engage in reckless behavior. Adolescents may become inconsistent

in their behavior, as they respond to reminders with withdrawal

and avoidance or overly aggressive behavior. Over time, there may

be increases in marital

discord and domestic violence.

Depressive

reactions can become quite serious, leading to a major decline in school

or occupational

performance

and learning,

social isolation, loss of interest in normal activities, self-medication

with alcohol or drugs, acting-out behavior to try to mask the depression,

and, most seriously, attempts at suicide.

Traumatic

grief can lead to the inability to mourn, reminisce and remember, fear

a

similar fate or the

sudden loss of other loved ones, and to difficulties in establishing

or maintaining new relationships. Adolescents may respond

to

traumatic

losses

by trying to become too self-sufficient and independent from parents

and other adults, or by becoming more dependent and taking

less initiative.

Coping

after Disaster

In

addition to meeting peoples basic needs for food,

water, shelter, clothing and medicine, there are several ways to enhance

people’s

coping. Physical:

Stress can be

reduced with

proper nutrition,

exercise and sleep.

People may need

to be reminded

that they

should take

care of themselves

physically to

be of help

to families and communities.

Emotional:

People need

to be reminded

that their

emotional reactions

are normal and expected,

and will decrease

over time.

However, if their

reactions are too

extreme or do

not diminish

over time,

there are professionals

who can be of

help. Social:

Communication with,

and support from,

family members,

friends, religious

institutions and the

community are very

helpful in coping

after a disaster.

People should

be encouraged to communicate

with

others, and to

seek and use

this support

where available.

Daily

Routines:

For children especially,

it is important

to restore

normal routines,

including mealtimes,

bedtime) as much

as possible. Children

feel more

safe and secure

with structure

and routine. Meeting

basic survival

needs, restoring

a sense of safety

and security, and providing

opportunities

for normal development

within the social,

family and community

context are important

steps to

the recovery of children

and adolescents.

source:

http://www.nctsnet.org/nccts/asset.do?id=603

This

project was funded

by the Substance

Abuse and Mental

Health Services

Administration (SAMHSA),

US Department of Health

and Human Services

(HHS). The views,

policies, and

opinions expressed

are those of the

authors and do

not necessarily reflect

those of SAMHSA

or HHS.

My

preparation to go to Sri Lanka was aided by a visit to Leland "Skip" and

Aew Whitney, Mill Valley residents who arrived in Colombo just after the

Tsunami. Synchronistically, Skip is on the board of OperationUSA; I read

about his family's journey in the local paper and then called him. He and

his wife graciously invited me to their home to tell me about what had happened

to them.

Mill Valley man helps in Tsunami zone

Jason Walsh, IJ reporter

Wednesday, January 19, 2005

- As a fund-raising board member of the international relief foundation

OperationUSA, Skip Whitney is used to helping disaster victims from a

distance.

But when fate placed the Mill Valley real estate developer at the center

of the Sri Lankan Tsunami devastation, Whitney found himself offering relief

in ways he never would have imagined. Whitney, his wife, Aew, and their

two daughters were vacationing in Southeast Asia during the holidays and

were due to fly from Bangkok to Colombo, Sri Lanka on Christmas Day. But,

because of a miscalculated departure time, the Whitneys missed their flight

- as well as the earth-shattering waves that rocked the island the next

day. "I have no doubt in my mind that if we had arrived on schedule,

we would be dead," Whitney said. Having heard only vague rumors of

a tidal wave and unaware of the full extent of the catastrophe, the Whitneys

caught the next flight to Colombo, arriving hours after the Tsunami swept

away the lives and homes of thousands of Sri Lankans. (The full story is

at http://opusa.org/press/marin_ind.htm)

As I prepare to go to Sri Lanka, I also solicit donations from friends

and the local schools. It is so hard to ask for money that instead

I ask for

crayons,

paper, scissors,

stickers, and children's band-aids. People are wonderful. Especially

moving are

the letters and drawings done by children here to give to

children in Sri Lanka. People I did not know were coming up to me, offering me crayons,

blessings,

good wishes, and respect. It is the admiration that throws me, as I

feel this is something I have to do; a call I must answer.

Friday, January 28, 2005

Today

is my flight, and at 4:00 a.m., I am still awake.

The alarm is set for 5:00 a.m. to begin the journey. Yet here I am,

packing and

racing around, fueled by adrenaline, anxiety and pressure to get everything

into one small bag. I am

shocked by my lack of preparation; why am I just now starting to pack? It

was hard, I had only known for a week and one half that I was going to Sri Lanka, and only found out yesterday I will be in the group going to Batticaloa,

affectionately known as “Batti”. I hear many jokes from my son

Colety that “Mom is going Batty!”, which feels very true at the

moment. We are allowed two bags, up to 70 lbs each, so my husband

Roy and son Colety packed the big suitcase with things for the children:

stickers, paper, letters and drawings from children here, zillions of children’s

band-aids, scissors, paper punches and balloons. 69 pounds, all donated.

Colety handed me a roll of money; between bake sales and

spare change

jars, the Novato Charter School had collected $200 for

the children of Sri Lanka.

7:09

am

Now the journey really begins. I missed the Airporter bus, so Roy had to race

me to the Larkspur terminal to catch another bus. Kate Chaos! I do get a little

tired of my frenzy at times, wishing for some of Roy's composure and serenity.

Finally, I am on the Airporter bus, heading to SFO. From there, I catch a plane

to LA,

switch airlines

and terminals, meet with the group, and then we fly

to Colombo, via

Tokyo and Singapore.

Our

team met in boarding area of Singapore Airlines, we range in age from 26

(our leader,

David) to the geriatric

one among us; me, age 50. We

bring a wide range of experience to the project. We will

find out more of what we will be doing in Singapore;

there

will

be training.

The

interventions

are specific, and directive. We cannot bring

anything aquatic, including in the stickers.

I would like to know

more about this;

it seems a paradox to

be directive, but avoid talking about the thing that

caused the trauma. Kind of the "you-know-who" Lord Voldemort

thing in Harry Potter.

We had received an e-mail from the Association for Play Therapy; our team is:

Janine

Shelby, Ph.D., B.C.E.T.S., RPT-S is a licensed psychologist and a clinical

faculty member

in the department of Psychiatry at UCLA. When she returns from Sri Lanka, she

will assume the position of Chief Psychologist in the Child Crisis Center,

Department of Pediatrics, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. She is a frequent consultant

for OperationUSA and other NGOs, a consultant for the National Center for

Child Traumatic

Stress, and a long-term American Red Cross volunteer. She appears on the National

Red Cross mental health training video. Dr. Shelby has lectured in and provided

relief to survivors in more than a dozen countries including those in the former

Yugoslavia, Russia, Western Europe, Asia, and Latin America. Her articles and

book chapters focus on posttraumatic interventions for traumatized children.

She is the President of the Foundation for the APT and in that capacity, worked

with OperationUSA, the Foundation Board, APT staff to design the project in

which we are participating.

Our

leader, David Bond MSW, has been collaborating with the National Center for

Child Traumatic Stress for the last nine months on Psychological First

Aid, an early response intervention protocol to be used in the immediate

aftermath of terrorist attacks and natural disaster. He works full time as

a psychotherapist at St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, CA. David

is a member of APT and has completed the requirements for the RPT credential,

for which he will apply upon obtaining his LCSW in March '05. He is currently

co-authoring a chapter on mental health practitioners' involvement in post-disaster

relief work.

Kate

Amatruda, MA, LMFT, Novato, CA: UC Berkeley Adjunct Faculty, Certified Sandplay

Therapist-Teacher, relief work during Loma Prieta Earthquake, 9/11 work in

schools, ARC Disaster Mental Health Member, CAMFT Trauma Response Network

Responder, Author of "Trauma, Terror and Treatment: PTSD in Children

and Adults".

Sharolyn Wallace Bowman, Ph.D. (Social Work), Tulsa, OK:

Professor at Tulsa Community College, 18 experience

in the childhood

grief field,

past experiences

working

in Russian orphanages doing related work, RPT-S (Registered

Play Therapist-Supervisor), Officer for OK Branch of

the APT

Valerie Hearst, LGSW, Brunswick, OH: Provided work to orphanage in Mexico

and Standing Rock Reservation, lived and studied in Mexico, social justice

trip to Puerto Rico and Dominican Republic, backpacked in Thailand, Mexico,

Guatemala, and Belize

Maria Parreno, Psy.D., Psychologist, Mission Viejo, CA:

Experience with relief work after Hurricane Iniki,

volunteer work in

orphanages in Mexico,

studied

in Israel during war, background growing up in Philippines

with missionary parents

Prabha Sankaranarayan, MS (Child Development), Pittsburgh,

PA: Therapist and Mediator, Snyder & Sankar Associates, 20 years experience working

with children, lived in India for 20 years, speaks Tamil (one of the

Sri Lankan languages),

NOVA training, currently writing PA plan for victims of a terrorist

attack

Jodi Smith, LCSW, Claremont, CA: social worker at Children’s

Hospital LA in ER and long-term wards for crisis and

trauma victims, Red Cross Volunteer, provided recreational

activities for orphans in Mexico

Joseph Wehrman, Ph.D. (Counselor Education), Aberdeen,

SD: Many years experience working in early childhood,

former member of

US Army where

he provided

on-site medical care to remote villages in Honduras,

lived and worked in Iraq providing

medical care to civilians and soldiers, worked 5 years

in

early childhood development, former Hall Director for

international students.

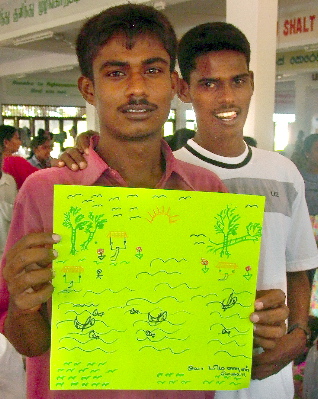

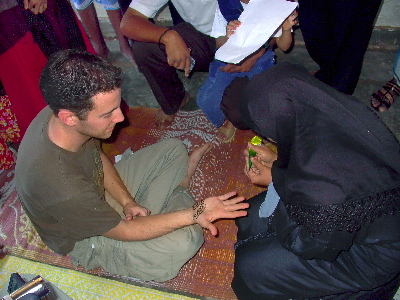

clockwise:

Kate, Joe, Prabha, Jodi, Sharolyn, David, Valerie, Janine and Maria

The

flights are endless. We left LA at 1:00 pm, went to Tokyo for a refueling.

In Tokyo, even though the layover was less than an hour,

everyone had to get off the plane, exit, go through security again,

wait in a long line, and get back on the plane. The security guards,

the ones who run your things through the x-ray machines, are all young

women, wearing red hats, red skirts and vests, with white blouses.

They wear high heels, as does every Japanese woman we see who works in the

airport. All the people I

encounter on the plane, in the airports, even at the security screening areas

are so touched that I am

going to

Sri Lanka,

that they

thank me. I accept their gratitude,

knowing it is soul food that will sustain me during the hard times.

The

LA to Tokyo flight was 11h 40m long. Tokyo to

Singapore is 7h 30m long. Singapore to Colombo 3h 35m. 22 hours and 45 minutes

in airplanes! Are we there

yet?

Back on the plane, seven+ more hours in the air until Singapore. I am getting

a bit squirrelly. It would be nice to go outside, breathe fresh air. In

Singapore, we stagger out of the airport, having been stamped through

immigration

(I was so happy to get a stamp in my new passport) and through the “nothing

to declare” line in customs. We get off the plane, into the

night, and realize we have no way of getting to the hotel. David

arranges

for a van, and we get to the hotel at 3:00 a.m., but which day I

have no idea.

Sunday

Hotel, shower, sleep. In the morning, David tells us “The Protocol”,

a series of exercises designed by Janine Shelby and her team to help

children master trauma. They are cognitive behavioral, with specific objectives

and

techniques. Each game has the objective, such as to:

*Normalize

reactions ("Yes, you are having a 'normal' reaction to

an 'abnormal' situation; whatever you are experiencing;

sleep difficulties, crying, anger, etc. is OK and normal."

In my work in the States, this is the stage

when I usually reassure a person that they are NOT crazy,

but

in Sri Lanka I don't know the cultural context for craziness.)

*Assess current coping mechanisms (and reinforce healthy ones),

*Assess and modify misattributions and cognitive distortions (such

as if the child feels that he or she did something

to cause the Tsunami)

*Decrease hyperarousal and panic symptoms (We hear that at one camp,

people feared that another Tsunami was coming. Some children were hurt

in the

stampede.)

*Increase self-soothing (breathe! breathe!)

*Identify and change intrusive re-experiencing, such as flashbacks

*Decrease isolation

and withdrawal and reinforce the ability to seek helpful

social support (ask for a hug, find someone to talk to, tell a grown-up)

*Decrease regressive behaviors by focusing on strengths and resources

*Identify loss reminders (water images, perhaps the aquatic stickers?)

and trauma triggers (such as loud noises, big waves, whatever you were

doing at

the time

at the

disaster)

*Finally,

to leave

the child with a sense of hope.

(Adapted from "Enhancing Coping Among

Young Tsunami Survivors: Culturally Approved Interventions

1/24/05 © Shelby,

Bond, Hall & Hsu, 2004)

I am

worried that our attempts to help will come to nothing; that we are offering

a band-aid for a gaping wound. A disaster that has killed so many cannot

be quickly overcome, particularly after so much war trauma.

The Tsunami is a holocaust that will affect Sri Lanka, the Indian Rim nations,

and the world for generations. And no technique will work if the hierarchy

of needs is not met; if the child is still in danger, hungry, or without

shelter. The first step in trauma work is to establish that the danger is

over, that the child is safe now.

Child

Trauma Intervention Model

Click

here for a power point presentation published by The National Resource

Center for Child Traumatic Stress, and adapted from:

Pynoos RS, Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM: (1998) A public mental health

approach to the post-disaster treatment of children and adolescents.

Psychiatric Clinics of North America 7:195-210.

Psychological

First Aid

Click

here for a power point presentation published by The National Resource

Center for Child Traumatic Stress, and adapted from: Pynoos RS, Nader

K: (1988) Psychological first aid and treatment approach to children

exposed to community violence: Research implications. Journal of

Traumatic Stress 1: 445-473. These

ideas are the basis of the techniques we used in Sri Lanka.

|

Why do we go

to play, and teach play techniques, in a cataclysm? As we get closer

to Sri Lanka, my mind struggles to

hold

the number who died. September 11 was about 3000, the Tsunami

was around 150,000 when I left. By the time I returned home the death

toll was 285,000; the count rises each day. I think we go to play with children

because play

is the first language, before children can verbalize, they play. Play allows

for the expression and healing of trauma. And we go because we, as humans,

want to do something for other humans who are suffering.

After working all day in Singapore, we have a few hours off. Prabha,

Valerie and I jump into a cab and go to Chinatown. We walk through

crowded streets; Chinese New year is almost here, so it is very

festive. Great shopping; I keep thinking I could make a killing

on EBay if

I had enough time and money, connections, and could carry everything.

This

must be how people make money; they buy things very cheaply,

sell high. What an alien concept for a therapist! Not this lifetime!

We check

out of the hotel and then leave for the airport to head

to Colombo, the biggest city in Sri Lanka. We

had arrived at the hotel

at 2:00 a.m., and we leaving at 8:00 p.m. the same day...how

many hours is that? 18 hours, most of it spent in training.

We

get to Colombo, where there is a strong military presence. The Army

is everywhere, running checkpoints and randomly pulling over

cars. We are pulled over and the soldiers shine a flashlight into

the car, mostly focusing

on Valerie. She is scared, keeps asking, “Should

I open the door?” Everyone

yells out, “No! No!” Later we find out we

were stopped because some of the women in our group have

short hair. The women fighters of the Liberation Tigers

of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), or Tamil Tigers,

are the only women in this country to have short hair. We

get to the hotel very late, it is 3:00 a.m. I am still awake,

wondering what is to come.

Monday

The next day is Monday, and we have another meeting, this time with Nimmi Gowrinathan,

an  OperationUSA worker,

a tall, brilliant and gorgeous Tamil woman who grew up in Los Angeles,

and is getting a Ph.D. in Political Science

from UCLA. She embodies her quote, "Leadership

is the capacity to translate vision into reality." Nimmi

orients us to the political and social structure of the country.

We learn about the

years of warfare, the riots, the discrimination

that the Tamil have felt at the hands of the Singhalese. (For more on this

conflict, please go to: Sri

Lanka: Ethnic Conflict & Civil War.)

OperationUSA worker,

a tall, brilliant and gorgeous Tamil woman who grew up in Los Angeles,

and is getting a Ph.D. in Political Science

from UCLA. She embodies her quote, "Leadership

is the capacity to translate vision into reality." Nimmi

orients us to the political and social structure of the country.

We learn about the

years of warfare, the riots, the discrimination

that the Tamil have felt at the hands of the Singhalese. (For more on this

conflict, please go to: Sri

Lanka: Ethnic Conflict & Civil War.)

There

is now a cease-fire in the war. We

learn that three days after we left Batticaloa that Kousalyan, the head

of the

Liberation

Tigers'

political

division

for the Batticaloa-Amparai district, was killed in an ambush

on the highway to Batticaloa Monday night February 7 around 7:45. Three

people who were traveling with him were killed and four were injured.

[source: TamilNet,

February 07, 2005 16:08 GMT]

I

wonder how this will affect the survivors of the Tsunami...how can they

begin to feel safe if the war comes again? I

cannot help but feel we left just in time, and, after viewing the devastation

wrought by nature, I would like

to bring the leaders of every country to view it, to tell them to

stop all wars. To help rebuild the planet. To stop senseless killing. To

use resources to end human suffering, not to increase it. (Of course,

I do keep all these sentiments to myself. One of the requirements of disaster

response

is to

be non-political,

non-denominational and nondiscriminatory.

We offer aid by need, not religion, ethnicity, political affiliation,

etc.)

We

have two teams, one headed to the South, the area that is primarily Buddhist

and Singhalese. My

team's destination is Batticaloa,

ground

zero

of

the

Tsunami,

and the place where there have been the least services provided. The East

is primarily Tamil, with the major religions being Hindu and Muslim. There

also seem to be pockets of Christianity throughout the country, and

the Eastern team will be staying at an orphanage started by Christian Missionaries.

We learn about the social customs; that women tie their hair up

or back at all times, that dress is modest,

with most

of the body covered. Women and girls wear earrings, and we hear

tales that if a woman has a hole in her ear, without an earring in it,

that the

Sri

Lankan

women will come

up and try to put an earring in the piercing. Irreverently we joke that

is a way to get more earrings. The henna paintings on hands, toe

rings and lovely sandals make sense if a woman's body is mostly covered;

for where else can she show her beauty?

We then briefly meet Janine Shelby, the play therapist who has

masterminded this project. She is very busy in Colombo, doing

many trainings. David asks

her some clarification questions and then she ends by giving us some

lovely words of encouragement for our mission. We race upstairs to

pack

up the

toys, and we are off to Batti, while the southern team heads toward Galle.

To Batticaloa is a long drive, at least 8 hours through the center of the

island. The roads are winding, the countryside incredibly  beautiful.

We see

elephants and monkeys, and go by some huge statutes of

the Buddha, towering over the town and countryside.

beautiful.

We see

elephants and monkeys, and go by some huge statutes of

the Buddha, towering over the town and countryside.

We are

regretting the ‘typical Sri Lankan breakfast’ of

very spicy curry we had this morning, as it is raising havoc

with our Western tummies. For bathrooms, we stop at “rest houses”,

which have little cafés with bathroom facilities. Almost

all have ‘English toilets’, but not all. The alternative

is a hole in the ground over which one squats. You stand on

little wooden

steps, pull your pants down and to the front, and squat down

low, trying not to splash yourself. There is a bucket of water

nearby that you

fill and dump in quickly, hoping to flush. We carry our own

toilet paper, as few rest houses have any.

We

are almost there when our driver, Ravi, pulls over. The van has a flat

tire. Out comes most of the luggage (and we

are not

traveling light; with clothing and supplies for the entire

10 day trip, as

well

as toys and art materials). We pile ourselves

and our

luggage

out of the car, and wait while Ravi tries to find the jack

to raise

the car. He finds most of it, missing however the crucial

piece that is the crossbar, with the socket end to remove the nuts

that hold

the tire on. Fortunately, we have stopped in a well-lit place

by the university,

and Ravi is able to borrow the cross piece of the jack.

We stand around swatting at mosquitoes until Nimmi’s father,

Roger, suggests that we put mosquito

repellant. We find later that the mosquitoes

are very resilient in Sri Lanka, finding the tiniest area

of skin not covered with DEET. Poor Valerie awakens one morning with

swollen eyelids; it

had not occurred to her to put the repellant on her eyelids. “DEET

UP” becomes a clarion call of the group, morning and evening.

We

are almost there when our driver, Ravi, pulls over. The van has a flat

tire. Out comes most of the luggage (and we

are not

traveling light; with clothing and supplies for the entire

10 day trip, as

well

as toys and art materials). We pile ourselves

and our

luggage

out of the car, and wait while Ravi tries to find the jack

to raise

the car. He finds most of it, missing however the crucial

piece that is the crossbar, with the socket end to remove the nuts

that hold

the tire on. Fortunately, we have stopped in a well-lit place

by the university,

and Ravi is able to borrow the cross piece of the jack.

We stand around swatting at mosquitoes until Nimmi’s father,

Roger, suggests that we put mosquito

repellant. We find later that the mosquitoes

are very resilient in Sri Lanka, finding the tiniest area

of skin not covered with DEET. Poor Valerie awakens one morning with

swollen eyelids; it

had not occurred to her to put the repellant on her eyelids. “DEET

UP” becomes a clarion call of the group, morning and evening.

We drive further, and are ‘almost there’ when the lights go out

on the van. This is very dangerous, as the road is narrow and the

people drive like maniacs. (It doesn't help my sense of mastery that Sri Lanka

has right hand drive; I keep being surprised by trucks and busses roaring

toward us on the right.) I feel as if I am in one of my son’s

video games, in which driving on a road means taking your life into your hands.

We

find

out later

that traffic fatalities are the leading cause of death in Sri Lanka,

followed by snakebites. We scrounge around in our luggage and find flashlights,

and

Nimmi hold a flashlight through the windshield as Ravi drives.

We are grateful for Ravi’s driving skills, as in the morning

we see that he has successfully navigated between the sea on one side and the

sewer trench

on the other. There are cows and goats to be avoided as well; somehow,

Ravi got us safely to the orphanage. Later we draft Ravi into our team

to work with the children; he knows how to play cricket!

We finally find our destination, St, John’s, an “American Ceylon” mission

that is an orphanage and school for children whose families have

died in the war. The children run out to greet Nimmi, who has visited before. Jeff

Greenwald wrote in his Field

Journals: A Journey Through the EastJanuary

19, 2005:

Jeff

Greenwald wrote in his Field

Journals: A Journey Through the EastJanuary

19, 2005:

"At the St. John’s Tsunami Relief and Rehabilitation

Center in Batticaloa, an Episcopal Reverend known as “Father J” (short

for Jeyanesan) is spearheading a multi-level effort that includes orphanages,

feeding

centers,

vocational training, and emergency relief supplies. (The popular Reverend was

already immersed in refugee work, providing for families displaced by the civil

war, when the Tsunami struck. Trained at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem,

Father J’s commitment to spiritual integration is immediately obvious;

St. John’s is the first church I’ve seen with a Jewish mezuzah

on its doorway.)"

We stumble upstairs to a large airy room and have dinner. This dinner,

to be repeated every night we are here, consists of cold

rice noodles, a sauce of coconut milk with a yellow spice in it, a curry

with

chucks of meat

and

bone, cut up and steamed carrots and green beans. We see

there are no utensils, so we follow Nimmi and Prabha’s

lead as we eat with our hands. One

never touches food with the left hand, ever, as that hand is used for

cleaning oneself. Joe, who is left handed, has to sit on his left hand

in order not to use it. I find that I cannot bring myself to eat any

fish

here, fearing, as the villagers do, that the fish might have eaten the

dead. There are charts in the papers to show what fish feed on, to reassure

us that the fish are safe to eat, but I can't make myself do it.

The

room upstairs is large and airy, and we think it will be a good place

to sleep. We find out, however, that only the men

will sleep

there. The

women go down to beds in the girl’s dormitory, bunk beds.

The girls flock to us, touching, talking in Tamil. They are

very curious about us, and call us “Auntie’,

which is a sign of respect given to an older woman. They

quickly

find

something to tease us about; for Valerie it

is her long nose (which to my Western aesthetic seems

on the short side), for me it is my lack of earrings,

as I

have removed

my earrings due to sore piercings.

They tug at their earrings and then reach for my sore

and inflamed ear lobes. I am determined to find earrings

that

are not as

heavy as the ones I was wearing,

and put antibiotic ointment on my earlobes before bed.

Getting ready for bed is a challenge. The girls are very modest,

and so I take my clothes with me to the shower. What shower?

Bathing take

place

in

a large

red bucket, with a smaller pitcher. You use the pitcher to

pour water over you, then soap down, and rinse again with water from

the pitcher.

There

is no hot water, and by the end of our stay there, I am in

agreement

with the ‘what

do you need hot water for in the tropics anyway?’ school

of thought. Right now, it is a shock, and I just cannot deal

with it.

After the plane trips, the long ride from Colombo, dinner eaten with my

hands, I confess to a moment of Western princessness; I want a real shower

and a room of my own! Not. Instead of braving the shower, the big red bucket,

I use wipes to clean myself, and try to change into sleeping clothes without

getting

them

wet, as

there is water everywhere in the floor. I do a little dance of rolling up

my pants leg, getting my feet in and out of my flip-flops, getting my legs

through the pants, without getting them wet. I am not quite successful,

so spend

the

first night with pants wet around the ankle. At least it is water from the

bath, and not the toilet!

All ready for bed, and I cannot sleep. I wander out and run into Selvie, the

lovely 30-year-old woman who is in charge of all the girls at the orphanage.

Selvie

speaks some English, and we find ourselves sitting on a bench, talking.

She is “amah” or mother to 175 girls! I compliment her,

and say that I an amah to only three children , and I cannot imagine

how she does it. The girls call her  “Selvie-amah”.

I tell her that I will be a grandmother in July, so my name becomes ‘Amahmah”,

or grandmother. Soon all the children call me “Amahmah”. Selvie

and I talk a bit, but every minute

a girl comes up to her for something; she is mother, nurse, soother, everything

to 175 girls. She also supervises the wardens, or young women

who serve as house mothers. They get to go home each night if they have

one, while Selvie-amah lives at the orphanage with the girls.

“Selvie-amah”.

I tell her that I will be a grandmother in July, so my name becomes ‘Amahmah”,

or grandmother. Soon all the children call me “Amahmah”. Selvie

and I talk a bit, but every minute

a girl comes up to her for something; she is mother, nurse, soother, everything

to 175 girls. She also supervises the wardens, or young women

who serve as house mothers. They get to go home each night if they have

one, while Selvie-amah lives at the orphanage with the girls.

Things have

become complicated

lately, as the Tamil Tigers, as a gesture of good will, released

their child soldiers to Unicef. Unicef turned the children over to the

orphanages, the place where they would be safest. Selvie has to integrate

adolescent

girls

who were soldiers into the community of proper Christian-schooled girls.

The child soldiers are the ones with short hair, and they stick together.

The culture

of the army and the culture of the orphanage are quite different, and I

wonder how long, if ever, it will take for the soldiers to blend in with

the cloistered

girls. Finally, I am sleepy enough to try to go to bed; so I find my bunk

in the dormitory and sleep. Our team begins to joke about the the

Southern team; we call them the 'resort humanitarians', because they are

eating in

restaurants and staying in hotels. (We find out later they visited 10 refugee

camps; hardly the 'resort' life we had fantasized for them!) What we lack

in comfort at the orphanage, however, is more than compensated for by the

warmth with which

we are embraced

by

the children and staff at St. John's.

Tuesday

I awake at 4:30 a.m. to the chatter and laughter of girls, the sounds of sweeping

and mopping. Bathing is done by seniority, so if the younger girls want to

bathe, they must

get

up very early to complete their chores before the ‘showers’ are

taken over by the older girls. I try to get back to sleep,

but my body has no idea of the day or the time. We have breakfast, a cold

fried

egg with bread and dried coconut flakes, very spicy and good. We are eating

with our hands, but cold egg defeats us, until we see that Prabha

has made an egg sandwich. We have tiny

bananas that grow in Sri Lanka; if the bananas in the States tasted this

good I would eat them every day. They grow in bunches and are sweet and creamy.

We also meet up with OperationUSA's

water team, who are giving people small hand pumps to filter water from their

wells. Carinne Meyer's report is online at http://www.operationusa.org/sri%20Lanka/field%20report.htm.

We get into the van to go meet the people who have arranged the training.

En route, we see houses damaged, and ask it is from the Tsunami. “No,

it is from the war. Fighting was here; this house was damaged by a

bomb, here

you see bullet holes.” We realize, that, other than flooded rice fields

(a huge concern, as the fields were inundated with salt water and sewage…how

will there be enough rice to feed the people?) we have yet to see Tsunami damage.

We are greeted by Father Paul Satkunayagam, Director and Co-founder of the “Butterfly

Peace Garden”. Children traumatized by the war

can come here to begin healing, and groups are run to

promote understanding and peace. I fall in love with The Butterfly Peace Garden,

and its mission:

The Butterfly Peace Garden is located in the Batticaloa district

of Sri Lanka, a region where many lives and communities have been profoundly

affected by a long-running civil war. For seven years now the Garden has

provided a sanctuary where thousands of children from villages and towns

throughout eastern Sri Lanka have come to play, cultivate the soil, care

for animals, practice arts such as music, painting, sculpture, ceramics,

theatre and learn basic elements of yoga, qigong and other body wisdom

exercises. Most importantly, the Butterfly Peace Garden is a place where

children have the opportunity to simply be kids again. As they make and

mend in the Garden, the children who pass through its gates become healers

in their communities, their nation and their world.

The

Butterfly Peace Garden opened its gates on September 11, 1996, and since

then it has been bringing together artists, peace-workers,

ritual healers and counselors with children from Batticaloa's various ethnic

and religious groups - Tamil, Muslim, Hindu, Christian - in an oasis of

peace amid the devastation of a civil war that has raged for two decades.

The children of the Butterfly Peace Garden are a remarkable tribe of magicians

who provide living testimony of the power of play as a tool in the lost

art of making peace."

(source: http://www.thestupidschool.ca/bpg/index2.html)

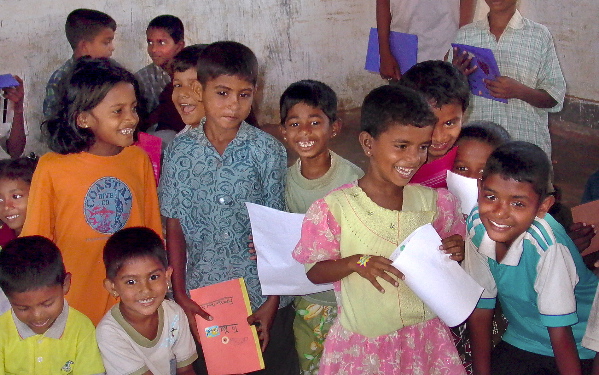

"Children

from six to sixteen years of age attend the Butterfly Garden for nine

months, one day a week, in groups of fifty drawn from the

local Tamil and Muslim populations. Many of them have endured profound

family loss and witnessed great horror: they are the children of terror.

In the Butterfly Garden these children are slowly restored to themselves

and to the world through play and storytelling, music and drama, the arts

of painting and puppetry and participation in the life of a garden. Reconstructed

rituals of genogram-making (The Mother-Father Journey) allow them to begin

telling the story of their families and their villages; group storytelling

allows them to find the narrative and dramatic power to represent new worlds

of their own making. Many of the Butterfly Garden staff were themselves

child victims of the war, and working there is for them a process of healing

and recovery. The work of the Butterfly Garden extends to the villages

in the countryside through a program of outreach and by means of the Butterfly

Garden Bus, which was a gift from the World University Services of Canada."(source: Geist

No. 33, 1999

We

are met here by a group of several men, called MEESAN (Modern

Economics Education and Social Affairs Network) who want to hear about what

we intend

to do, and to make sure it is culturally sensitive. Too many Westerners

have come in to work and apparently, they either leave the children a wreck

(we

hear of someone who came to do EMDR with the children, and left them all

sobbing and unglued as she or he caught a flight back to the States) or just

come in and lecture the workers about what the children need. We are

determined to be different. We decide the best use of our time and talents

is to ‘train

the trainers’, and so a group of 18 people who work with children

are invited to come to our trainings. David explains the exercises and

play activities

to the group.

The men also review our exercises, cognitive behavioral puppet shows and

games that are geared toward mastery of trauma, and agree that they

will not disrupt

the culture. Where we are, in the East, most of the children are Hindu or

Muslim. The team in the South is dealing with Buddhist children.

Each

team finds quickly that we need to modify certain elements of our games.

That afternoon we meet with the trainers to find out their needs, teach

them our techniques, and get to know each other. I become the designated

icebreaker,

and while the rest of the team sets up, I offer each person a cinnamon Altoids,

and then go around and put a butterfly sticker on each person's hand. I make

eye contact when I do, and see incredible wisdom and pain in their

eyes. They are called “animators” (no one seemed to know

why) and they work with the children. Until the Tsunami, their role

was to help the children

with war trauma.

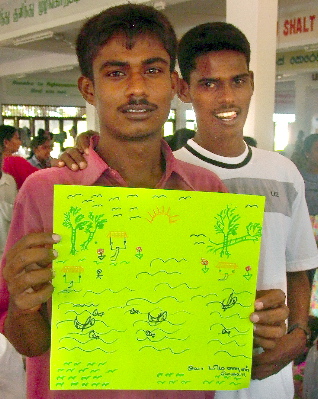

As I hand out the stickers, they tell me that a butterfly is called “Vannathupoochi” in

Tamil, and I try to say it to each person. When I get toward the end of

the group, someone started singing a song about “Vannathupoochi” in

Tamil, which amazingly, goes to the tune of “Frère Jacques”.

I try to sing along, bringing gales of laughter from the people. This song

becomes my theme, and somehow, by osmosis, the children at the orphanage

start singing it to me as well. It is perfect, and when I tell the trainers

how the

butterfly motif has appeared spontaneously in the psyches of children with

whom I have worked that are facing death, they nod in agreement. I tell

them of the children in the concentration camps

who had

carved butterflies with their fingernails in the wood, and again they nod

"yes". They know firsthand the grave loss and despair that seems to summon

the butterfly.

Sri Lankan nodding “yes” is like that of a dancer; somehow, the

head goes back and forth, and the neck moves sideways. When I try it, I feel

like I do when I try to show children how an owl can look backwards; my neck

muscles cannot do this at all! More gales of laughter when we try to nod ‘yes’ to

the trainers. This learning to nod becomes David’s theme with the trainers;

they tease him as he good humoredly tried to do it. We learn there is a subtle

difference between nodding ‘yes’ and ‘I don’t know” and “no”;