|

Part

I Spousal

and Partner Abuse |

2008

If

you are in danger call 911 or |

| This course provides a comprehensive overview of domestic violence, details numerous research studies and findings from state and local domestic violence programs, and reviews case experiences of advocates who work with victims and batterers. Protocols and policies for criminal justice system, legal, and coordinated community-based interventions are also examined, along with summaries of federal and state laws relevant to domestic violence prevention and interventions. Aspects of the physical, psychological, and financial impact of domestic violence on its victims, and on children who witness violence, are addressed. |

Around

the world at least one woman in every three has been

beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her

lifetime. Most often the abuser is a member of her own

family. Ending violence against women, a report from the Center for Communications Programs, Johns Hopkins University |

Approximately

1.5 million women and 834,700 men are raped and/or

physicallyÊassaulted

by an intimate partner each year. Center for Disease Control |

Children

who witness domestic violence are more likely to exhibit

behavioral and physical health problems including depression,

anxiety and violence towards peers. Adolescents are also

more likely to attempt suicide, abuse drugs and alcohol,

run away from home, engage in teenage prostitution and

commit sexual assault crimes. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services |

| More

women than men experience intimate partner violence. According

to the National Violence Against Women Survey, 1 out of 4

U.S. women has been physically assaulted or raped by an intimate

partner; 1 out of every 14 U.S. men reported such an experience Center for Disease Control |

This

15 unit course

addresses the

'red flags'

assessment,

detection, and

intervention strategies including

community resources,

cultural factors,

substance abuse,

same gender abuse dynamics, and

treatment regarding

spousal or partner

abuse

and may be taken in fulfillment of the ![]() CA

BBS and BOP mandated continuing abuse requirement

CA

BBS and BOP mandated continuing abuse requirement

Increasingly,

gender-based violence is recognized as a major public health concern

and a violation of human rights. The effects of violence can be

devastating to a woman's reproductive health as well as to other

aspects of her physical and mental well-being. In addition to

causing injury, violence increases women's long-term risk of a

number of other health problems, including chronic pain, physical

disability, drug and alcohol abuse, and depression. Women with

a history of physical or sexual abuse are also at increased risk

for unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and

adverse pregnancy outcomes. Yet victims of violence who seek care

from health professionals often have needs that providers do not

recognize, do not ask about, and do not know how to address."(Ending

violence against women, a report from the Center for Communications

Programs, Johns Hopkins University at http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11edsum.shtml)Volume

XXVII, Number 4

December, 1999

Series L, Number 11

Issues in World Health

The best way to uncover a history of abuse in female clients is

to ask about it. Nonetheless, several types of physical injuries, health

conditions, and client behavior should raise health care providers' suspicion

of domestic violence or sexual abuse. When these signs, or 'red flags,'

are present, providers should be sure to ask their clients about possible

abuse, remembering to be empathic and respectful of the client's privacy.

| Chronic, vague complaints that have no obvious physical cause, | Pregnancy of unmarried girls under age 14, | ||

| Injuries that do not match the explanation of how they occurred, | Sexually transmitted infections in children or young girls, | ||

| A male partner who is overly attentive, controlling, or unwilling to leave the woman's side, | Vaginal itching or bleeding, | ||

| Physical injury during pregnancy, | Painful defecation or painful urination, | ||

| Late entry into prenatal care, | Abdominal or pelvic pain, | ||

| A history of attempted suicide or suicidal thoughts, | Sexual problems, lack of pleasure, | ||

| Delays between injuries and seeking treatment, | Vaginismus (spasms of the muscles around the opening of the vagina), | ||

| Urinary tract infection, | Sleeping problems, | ||

| Chronic irritable bowel syndrome, | A history of chronic, unexplained physical symptoms, | ||

| Chronic pelvic pain. | Having difficulty with or avoiding pelvic exams, | ||

| Problems with alcohol and drugs, | |||

| Sexual 'acting out,' | |||

| Extreme obesity. | |||

Fuente: Center for Health and Gender Equity y Family Violence Prevention Fund (460). |

|||

source: http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11pullout.shtml#top

What

are the warning signs of an abusive spouse or partner?

According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the following

signs are common predictors of abuse:

violent family life;

use of violence or force to "solve" problems;

use of alcohol or other drugs;

strong traditional ideas about the role of husband and wife;

jealousy of a spouse or partner's other relationships;access to weapons, such as knives or guns, and threats to use them;

expectation that a spouse or partner will follow orders or advice;

mood swings with extreme highs and lows;

rough treatment of a spouse or partner

http://www.mentalhealth.org/highlights/october2003/domestic/

Please go to: Potential Problems for Psychologists Working with the Area of Interpersonal Violence

While this article is written specifically for psychologists, it has important information about the dangers of working with spousal and partner abuse for all mental health professionals.

"Interpersonal violence cases have the potential for the most dangerous outcomes. It is important for psychologists in their various roles to ensure safety, prevent harm whenever possible (General Principle E, F, and ES 1.14), and to warn clients or others in danger. In all interpersonal violence cases or alleged cases, it is crucial that some type of assessment of the abuse or violence be conducted, and the risk of harm be ascertained. It is also important that all clinical cases be evaluated or screened to determine the likelihood of present or past abuse or violence....

Psychologists should have an up-to-date awareness of the ethical and legal standards that affect their practice. Knowledge of confidentiality and exceptions to confidentiality is particularly important when working with clients who may be involved with violence." Please go to APAonline for the complete article at http://www.apa.org/pi/pii/professional.html?CFID=2636885&CFTOKEN=52026085

California

psychologists please go to: http://www.psychceu.com/ca-bop_law_summary.pdf

for State Of California Department Of Consumer Affairs Board Of Psychology Summary

Of California Laws Relating To The Practice Of Psychology.

![]()

You may need to

get Adobe Acrobat to view this and other pdfs; please go to http://www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/readstep2_allversions.html

.

"Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists are not mandated reporters

of domestic violence. If an LMFT reports domestic

violence, it is a breach of confidentiality, regardless of the

work setting or employer. As reported in the November/December 1994

issue of The California Therapist, LMFTs are not to report domestic

violence, even though there still seems to be confusion about this subject

in practice.

California Penal Code §1160(a) states that a health practitioner

who is providing medical services for a physical condition is a mandated

reporter. LMFTs do not provide services for physical conditions. Therefore,

LMFTs do not report domestic violence. There is no exception for LMFTs

in settings where physical health treatment is provided. There is no

exception for LMFTs even if your employer has a different policy. No

local policy of any agency or county takes precedence over state law."

(Pelchat, Z., "LMFTs Do Not Report Domestic Violence", January/February 2001, The California Therapist)

Confusion -Do you report Spousal or Partner abuse if the patient is an elder, as Elder Abuse is mandated for reporting in California? For more information, please go to ADULT PROTECTIVE SERVICES MANDATED REPORTERS . (In this situation, I would call the free legal counsel available through my professional organization.)

"the right to privacy ends where the public peril begins" and that "clear and immediate probability of physical harm" to others allows for the breaking of confidentiality.

"There

are six pieces that must be documented when a patient makes a serious

threat of violence before a Tarasoff warning is indicated. They are:

1. a patient

2. tells

3. you, the therapist (or your psychological assistant)

4. a serious threat

5. of physical violence

6. against a reasonably identifiable victim

The consequences of not following the 'duty to warn' include liability,

as you may be held responsible for any harm done, not only to the intended

victim, but any others who are injured when the patient tries to harm

the intended victim.

Document everything if you are going to invoke Tarasoff. This includes

the stated threat, the means to carry it out, your attempts to locate

the intended victim, as well as notifying the appropriate law enforcement."

(Pelchat, Z.,

"Tarasoff for Clinicians: A User's Guide to the Law", November/December

2001, The California Therapist)

For more on this, go to "Summary of Final Rule Providing Standards

for the Privacy of Patient Records", at APAonline, at

http://www.apa.org/practice/medrecsum.html

As

the laws are different for each state and license, you

MUST know what the legal and ethical obligations are for you,

in your state, with your license.

Please go now and do a search for your state and license. (We will

ask you for this information on the post-test.) Go to http://www.feminist.org/911/crisis.html as

they have links for each state.

(If you do not know how to search, we recommend Google. Just put in the relevant words, such as LCSW mandated reporter domestic violence MA; you will get a page of links. See if you can find the answer. An example is:

For Massachusetts Social Workers, this information was found at: The National Association of Social Workers - Massachusetts Chapter:

The NASW Code of Ethics Applied: Confidentiality at http://www.naswma.org/content.asp?contentID=17&topicID=58

Keep abreast of legal statutes affecting practice. For instance, knowledge or strong suspicion of child or elder abuse must be reported to DSS no matter how much you worry about the effect such a report may have on your relationship with your client. There is, however, no mandated reporting of spousal abuse. Duty-to-warn standards also supersede confidentiality. In cases where you are told of a plan to harm another individual, you may be required to break confidentiality in order to protect the intended victim.

Please

e-mail us any relevant links

that you find, so we may include them in future versions of this course.

Thank you!

It is advisable to consult with an attorney if you have questions or concerns about your obligation in your state.

Physical

violence in intimate relationships almost always is accompanied by psychological

abuse and, in one-third to over one-half of cases, by sexual abuse (59,

75, 131, 258, 272). For example, among 613 abused women in Japan, 57%

had suffered all three types of abuse—physical, psychological, and

sexual. Only 8% had experienced physical abuse alone (485). In Monterrey,

Mexico, 52% of physically abused women had also been sexually abused by

their partners (191). In Le'n, Nicaragua, among 188 women who were

physically abused by their partners, only 5 were not also abused sexually,

psychologically, or both (131).

Most women who suffer any physical aggression generally experience multiple

acts over time. In the Le'n study, for example, 60% of women abused

in the previous year were abused more than once, and 20% experienced severe

violence more than six times. Among women reporting any physical aggression,

70% reported severe abuse (130). The average number of physical assaults

in the previous year among currently abused women surveyed in London was

seven (308); in the US in 1997, three (436).

In surveys of partner violence, women usually are asked whether or not

they have experienced any of a list of specific actions, such as being

slapped, pushed, punched, beaten, or threatened with a weapon.

Asking behavioral questions—for example, “Has your partner

ever physically forced you to have sex against your will?”—yields

more accurate responses than asking women whether they have been “abused”

or “raped” (127). Surveys generally define

physical acts more severe than slapping, pushing, shoving, or throwing

objects as “severe violence.”

Measuring “acts” of violence

does not describe the atmosphere of terror that often permeates abusive

relationships. For example, in Canada's 1993 national violence survey

one-third of women who had been physically assaulted by a partner said

that they had feared for their lives at some point in the relationship

(378). Women often say that the psychological abuse and degradation are

even more difficult to bear than the physical abuse (57,

58, 96).

http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11chap2_1.shtml

|

On This Page Intimate partner violence—or IPV—is actual or threatened physical or sexual violence or psychological and emotional abuse directed toward a spouse, ex-spouse, current or former boyfriend or girlfriend, or current or former dating partner. Intimate partners may be heterosexual or of the same sex. Some of the common terms used to describe intimate partner violence are domestic abuse, spouse abuse, domestic violence, courtship violence, battering, marital rape, and date rape (Saltzman, et al. 1999). CDC uses the term intimate partner violence because it describes violence that occurs within all intimate relationships. Some of the other terms are overlapping and may be used to mean other forms of violence including abuse of elders, children, and siblings.

Back

to Top Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in the United States. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. Available on-line at http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/ipv_cost/ipv.htm. Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, Melissa KJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health 2000;90(4):553–9. Felitti V, Anda R, Nordenberg D, Williamson D, Spitz A, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1998;14(4):245–58. Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Violence and reproductive health; current knowledge and future research directions. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2000;4(2):79–84. Holtzworth-Monroe A, Bates L, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research on husband violence: part I: maritally violent versus nonviolent men. Aggression and Violent Behavior 1997;2(1):65–99. National Research Council. Understanding Violence Against Women. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 1996. p. 74–80. Paulozzi LJ, Saltzman LA, Thompson MJ, Holmgreen P. Surveillance for homicide among intimate partners—United States, 1981–1998. CDC Surveillance Summaries 2001;50(SS-3):1–16. Roizen J. Issues in the epidemiology of alcohol and violence. In: Martin SE, editor. Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence: Fostering multidisciplinary perspectives. Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1993. p. 3–36. NIAAA Research Monograph No. 24. Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 1999. Straus MA, Gelles, RJ, editors. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick (NJ): Transaction Books; 1990. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Report for grant 93-IJ-CX-0012, funded by the National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington (DC): NIJ; 2000. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Report for grant 93-IJ-CX-0012, funded by the National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control. Washington (DC): NIJ; 2000. Wisner CL, Gilmer TP, Saltzman LE, Zink TM. Intimate partner violence against women: do victims cost health plans more? Journal of Family Practice 1999;48(6):439–43. |

AM I BEING ABUSED? Checklist Look over the following questions. Think about how you are being treated and how you treat your partner. Remember, when one person scares, hurts or continually puts down the other person, it’s abuse. Does your partner.... ____Embarrass or make fun of you in front of your friends or family? ____Put down your accomplishments or goals? ____Make you feel like you are unable to make decisions? ____Use intimidation or threats to gain compliance? ____Tell you that you are nothing without them? ____Treat you roughly - grab, push, pinch, shove or hit you? ____Call you several times a night or show up to make sure you are where you said you would be? ____Use drugs or alcohol as an excuse for saying hurtful things or abusing you? ____Blame you for how they feel or act? ____Pressure you sexually for things you aren’t ready for? ____Make you feel like there "is no way out" of the relationship? ____Prevent you from doing things you want - like spending time with your friends or family? ____Try to keep you from leaving after a fight or leave you somewhere after a fight to "teach you a lesson"? Do You... ____Sometimes feel scared of how your partner will act? ____Constantly make excuses to other people for your partner’s behavior? ____Believe that you can help your partner change if only you changed something about yourself? ____Try not to do anything that would cause conflict or make your partner angry? ____Feel like no matter what you do, your partner is never happy with you? ____Always do what your partner wants you to do instead of what you want? ____Stay with your partner because you are afraid of what your partner would do if you broke up? If any of these are happening in your relationship, talk to someone. Without some help, the abuse will continue. Your Domestic Violence Survival Kit Protecting Yourself in a Dangerous Relationship Print and Carry with you If you are still in the relationship: Think of a safe place to go if an argument occurs; avoid rooms with no exits (bathroom) or rooms with weapons (kitchen). Think about and make a list of safe people to call. Keep change with you at all times. Memorize all important numbers. Establish a code word or sign so that family, friends, teachers or coworkers know when to call for help. Think about what you will say to your partner if he or she becomes violent. Remember you have the right to live without fear and violence. Your Personal Safety Plan The following steps are my plan for increasing my safety and preparing to protect myself in case of further abuse. Although I can't control my abuser's violence, I do have a choice about how I respond and how I get to safety. I will decide for myself whether and when I will tell others that I have been abused or that I am still at risk. Friends, family and coworkers can help protect me, if they know what is happening and what they can do to help. To increase my safety, I can do some or all of the following: When I have to talk to my abuser in person, I can ________________________________ When I talk to my abuser on the phone, I can ___________________________________ I will have a code word for my family, coworkers or friends, so they know when to call for help for me. My code word is ________________ When I feel a fight coming on, I will try to move to a place that is lowest risk for getting hurt such as (at work)__________, (at home)____________, (in public)_________________. I can tell my family, coworkers, boss or a friend about my situation. I feel safe telling: ______________________________________________ I can use an answering machine or ask my coworkers, friends or other family members to screen my calls and visitors. I have the right to not receive harassing phone calls. I can ask to help screen my phone calls. (home)________ (work) _____________ I can keep change for phone calls with me at all times. I can call any of the following people for assistance or support if necessary and can ask them to call the police if they see my abuser bothering me. Friend _______________________________________ Relative ______________________________________ Coworker _____________________________________ Counselor _____________________________________ Shelter _______________________________________ Other ________________________________________ When leaving work I can: _________________________________________________ When walking, riding or driving home, if problems occur, I can: _____________________ I can attend a support group for women who have been abused. Support groups are:_______ ____________________________________________________________________ Telephone numbers I need to know: Police/Sheriff's Department: ___________________ Probation officer: _________________ Domestic violence/sexual assault program:________________ Counselor: ________________ Clergy: _____________________ Lawyer: ___________________ Other: ____________________ After you have left the relationship: Change your phone number. Screen calls. Save and document all contacts, messages, injuries or other incidents involving the batterer. Change locks if the batterer has a key. Avoid staying alone. Plan how to get away if confronted by an abusive partner. If you have to meet your partner, do it in a public place. Vary your routine. Notify school and work contacts. Call a shelter for battered women. The National Domestic Violence Hotline 1-800-799-SAFE

(7233) 1-800-787-3224 (TDD)

|

http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11chap3.shtml

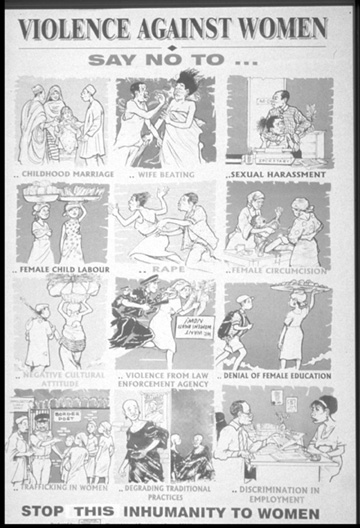

Women, Law and Development Centre Nigeria

As this poster from Nigeria illustrates, violence against women takes many forms. Often, social and cultural norms condone gender-based violence.

You may be becoming or already are a victim of abuse if you:

If you are abused:

Look out for men who:

http://www.womanabuseprevention.com/html/abuse_signs.html

Things You Can Do To Stay Safe

Are you a child or teenager living in a home where violence occurs, either

between your parents or your brothers and sisters?

If you answered yes, you should know that as a child living in an abusive

household there are things that you can do to be safe.

You should not get in the middle of a fight between your parents or brothers

and sisters, even if they ask you for help. This will not make the fighting

stop, and you may get hurt.

If you want to help the abused person ask how or simply dial 911, learn

important numbers including family and local emergency agencies, and go

over a safety or escape plan with the abused person.

Tips on calling 911:

When dialing 911 there are ways to make the response quicker, and to ensure

your safety. First tell the operator your name and address, tell them

what is going on and where this is happening, and you should tell them

if this has happened before.

Before an emergency situation occurs you should know:

*Your full name

*Your complete address including city, state and zip code

*Your entire phone number with area code

*What situations will lead you to call 911. If domestic violence is occurring

in your house, you might want to make up a code word with the abused parent

or sibling. If he/she uses that word then you will call 911

During an emergency situation you should know:

*Dialing 911 can reach police, the fire department or ambulance

*Try to remain calm

*When the 911 operator answers, state the problem briefly and give your

full name and address

*Do not hang up the phone until the operator says to

Asking For Help

Asking for help does not mean you are going to get in trouble, but if

you do get into trouble call the police again or speak to a trusted adult.

Trusted adults can include your teachers, ministers, coaches or family

members. If your parents are separated, divorced or never married, the

school should know who can and cannot pick you up from school. If the

person who is abusive visits your school or tries to remove you, please

notify a teacher or the principal. They can help you decide what to do

next.

If you need someone to talk to, there is help for you at school or somewhere

in your community.

Don't Blame Yourself

As a child living in an abusive home, it’s easy to blame yourself

and think that what is going on is your fault. You think "If I would

be quieter, better at school, neater, more respectful and so on and so

on." Living there, you must know that no matter how hard you try,

it does not stop. You are not the problem.

If the abused person or the abuser at some time needs to leave the home

for safety reasons, remember again this is not your fault. The abuser

in your home has a problem. This person chooses to be violent or controlling.

There is help for abusers. This help can come after you call the police

or through counseling. The abuser needs to learn that he/she does not

have the right to use violence, threats or intimidation to get what he/she

wants. Staying may seem dangerous or even stupid to you, but there are

reasons and some of them include your safety. Talk to the abused person,

talk to a teacher, or call a hotline and make a safety plan. For more

help, or someone to talk to please check the links section or call the

National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE.

-------------

Department of Health and Human Services:

HELPING CHILDREN WHO WITNESS DOMESTIC

VIOLENCE

HHS Secretary Tommy G. Thompson today announced a new initiative

to help children who witness domestic violence to develop into healthy,

well-adjusted adults and prevent the cycle of violence from continuing

from one generation to the next.

The initiative, called "Safe and Bright Futures

for Children," will incorporate evidence-based

practices such as treatment for child and adolescent trauma, mentoring

and mental health services while also addressing risk and protective factors

to negate the cyclical effects of violence. It will encourage the

integration of these services at the local and regional level by building

collaborations of community, faith-based or other programs that identify,

assess, treat and provide long-term services.

"Each year, there are nearly 700,000 documented incidents of domestic

violence that threaten the well-being of children and families across

our nation," Secretary Thompson said. "This new effort will

provide preventive services and support to help children affected by this

violence to enjoy a safe and bright future and to break the cycle of violence.

We want to provide our youth with the skills and tools they need to make

healthy choices in their lives."

Research has found that activities that involve

and empower youth in their families, schools and communities can help

protect them from harm. Under the new effort, HHS expects to provide funding

for demonstration projects nationwide to serve children and adolescents

who witness or are exposed to domestic violence.

A significant percentage of children who

witness domestic violence eventually become abusers or victims of abuse.

In addition, children who witness domestic violence are more likely to

exhibit behavioral and physical health problems including depression,

anxiety and violence towards peers. Adolescents are also more likely to

attempt suicide, abuse drugs and alcohol, run away from home, engage in

teenage prostitution and commit sexual assault crimes.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services • 200 Independence

Avenue, S.W. • Washington, D.C. 20201

http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2003pres/20031008.html

Please go to the:

WORKSHOP

ON CHILDREN EXPOSED TO VIOLENCE:

CURRENT STATUS, GAPS, AND RESEARCH PRIORITIES

WORKSHOP SPONSORS:

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

Fogarty International Center (FIC)

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR)

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)

National Institute of Justice (NIJ)

Department of Justice

Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP)

Department of Education

|

This information packet provides an introduction to the dynamics, prevalence and consequences of teen dating violence. The packet explores issues specific to teen dating violence, examines current provision of support services for teens and presents information about a variety of promising prevention /intervention strategies. While some awareness materials such as booklets, checklists and posters are included, the intent of packet contents is to examine some of the key dating violence issues currently facing teens and their advocates. Material within the packet has been organized into categories according to current issues (see the Cover/Table of Contents). Following the Overview, a Key Issues section begins with a brief review of Teen Dating Violence Public Policy, followed by information about Health Concerns for Teen Dating Violence Survivors, Use of Violence by Girls and Boys in Heterosexual Teen Relationships, Service Provision Challenges and Changing Approaches in Prevention. The packet includes articles and referral information designed to promote increased knowledge on each key issue and concludes with a Fact Sheet, Statistics Sheet, Bibliography, and Resource Lists designed to help readers gain to access Prevention/Education, Intervention Programs and Direct Service Tools, Websites and Videos.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SCREAMS IN A VACUUM Gay

male domestic violence and abuse

shares a great deal of similarities with its heterosexual

counterpart: frequency (approximately one in every four couples);

manifestations (emotional, physical, financial, sexual, etc);

co-existent situations (unemployment, substance abuse, low self-esteem);

victims' reactions (fear, feelings of helplessness, hyper vigilance);

and reasons for staying (love, can work it out, things will change,

denial) are some examples. But significant differences, unique

issues and deceptive myths are just as much part of the phenomenon.

Intra-lesbian Violence By: Lori Haskell Recently, the extent to which domestic violence is a gender issue has been the subject of debate, since violence takes place within lesbian relationships. Gender is socially constructed and, as such, is always present in human relationships. Gender is relevant to men's violence against women and to intra-lesbian battering, but gender plays out differently in the significantly different relational contexts. Because lesbian battering doesn't neatly fit into the theoretical model of heterosexual battering, it doesn't mean that we throw out our theory. A more productive approach would be to understand the continuities and discontinuities between violence in heterosexual and lesbian relationships. Obviously, there will be some similarities in why acts of physical violence are perpetrated in intimate relations, but there will be many differences as well between heterosexual and gay/lesbian relationships. The only way to develop a more complete and nuanced picture of the underlying dynamics is to contextualize our understanding; otherwise we may take the regressive step of proposing a purely psychological model which does not take social relations into account. Instead, we need to understand the forces of systemic subordination, such as heterosexism, sexism, racism, classism and differences in abilities, as these contribute to the shape violence in intimate relationships may take. Specifically, how are lesbian lives shaped, constrained and limited by the systems of oppression? To what degree and finally with what effect? We need to question whether the form and function of lesbian battering is the same as 'wife abuse' perpetrated by men against their female intimates. What both forms of abuse may share is the function of social control, albeit for entirely different reasons. Heterosexual men internalize the belief of male dominance, that is, that they are entitled to control their female partners in order to keep their privilege and dominance in place. Men's violence against women in intimate relationships is inextricably a part of male entitlement, a belief in men's right to control women and in male superiority. These beliefs are widely reinforced institutionally throughout our culture. Unlike heterosexual woman abuse, there are no wider cultural messages reinforcing lesbian superiority over their partners, or women's entitlement to exert control over their intimates to explain why some women may abuse their female partners. In a lesbian relationship, on the other hand, the sense of isolation, invisibility and silence that is often the result of homophobia and heterosexism increases the dependency of the partners on each other. This increased dependency and isolation may result in an increased need to control one's partner, especially in relationships where one lesbian passes as heterosexual while her partner does not, or when one partner seeks more independence or separation. These disruptions may pose a threat to the integrity of the relationship. This could result in a lesbian partner responding with emotional or physical violence as an attempt to control her partner and keep her in the relationship. Additionally, a consequence of internalized sexism and homophobia may very likely be decreased self-worth and possibly self hate. This sense of powerlessness and worthlessness that a lesbian may feel about herself can be transferred onto her partner. It is much easier to batter and violate someone you view with contempt, especially when that contempt is socially produced and reinforced through homophobia. Internalized homophobia and sexism are manifestations of oppression. Although these oppressions have clear psychological dimensions in terms of how they are manifested, they are still socially constructed, and gender is always implicated. This distinction between seeing a phenomenon as socially constructed versus one that is purely psychological is not just a matter of semantics. How we theorize and understand the problem gives direction to how we develop our strategies and interventions. If we see lesbian battering as a consequence of psychological problems, the approach would be to offer treatment to the individual, devoid of any attention to the social context of the relationship. If, however, we see the problem as socially constructed as a result of the intersections of different oppressions, then our approach is also one of social change, including creating safer communities, connection and support for lesbians, while working to eradicate homophobia and heterosexism. It is unlikely that physical violence, coercion and control characterize lesbian relationships to the same extent that repeated research has shown in random samples of women's experiences in heterosexual relationships. There is no historical and contemporary legacy legitimizing physical violence in lesbian relationships as there is underpinning men's violence against women in intimate relationships. Clearly this is a fundamental difference in the gender dynamics at play in violence in heterosexual and lesbian/gay relationships. We need a body of methodologically sound empirical research to document the pervasiveness, scale, effect and impact of violence in lesbian relationships. This would help reveal the differences and similarities between lesbian and heterosexual relationships. Lori

Haskell is a psychologist, researcher and educator on issues

of violence against women and children. |

| Contact: Gay Partner Abuse Project 416.876.1803 |

To read the course material, go now to: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT) Communities and Domestic Violence: Information and Resources by Mary Allen for the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRCDV) (2007) Domestic violence in LGBT communities is about abuse of power, manipulation, exploitation, oppression and barriers to service. This collection has been designed for domestic violence program advocates, activists working in LGBT communities and those wishing to become allies.

|

Women

consistently cite similar reasons that they remain in abusive relationships:

fear of retribution, lack of other means of economic support, concern

for the children, emotional dependence, lack of support from family and

friends, and an abiding hope that “he will change” (10, 131,

330, 413, 488). In developing countries women cite the unacceptability

of being single or unmarried as an additional barrier that keeps them

in destructive marriages (169, 368, 488).

At the same time, denial and fear of social stigma often prevent women

from reaching out for help. In surveys, for example, from 22% to almost

70% of abused women say that they have never told anyone about their abuse

before being asked in the interview (see Table 3). Those who reach out

do so primarily to family members and friends. Few have ever contacted

the police.

http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11chap2_3.shtml

A wide range of studies agrees on several factors at each of these levels that increase the likelihood that a man will abuse his partner:

Questionnaire:

ARE YOU BEING ABUSIVE?

Below are a series of questions that may assist you in understanding if your behavior is abusive or violent. Domestic violence includes not only the more visible physical manifestations but also includes verbal, emotional and sexual forms of behavior. If you answer yes to any of these questions you may wish to seek assistance through the Gay Partner Abuse Project or another source of professional assistance. Recognizing your behavior is the first step towards making change.

http://www.gaypartnerabuseproject.org/html/abusive.html

| PHASE

1. TENSION BUILDING |

PHASE

2. ACUTE BATTERING |

PHASE

3. KINDNESS AND LOVING BEHAVIOR |

| Victim compliant, good behavior. Batterer

experiences increased tension. |

Batterer

unpredictable, claims loss of control. |

Batterer

often apologetic, attentive. Victim has mixed feelings. Batterer is manipulative. Victim feels guilty and responsible. Batterer promises change. Victim considers reconciliation *court: often the victim must appear in court during this time |

|

Note:In

an effort to disrupt the idea that only men perpetrate abuse,

the pronouns used on this web site and in our literature that

refer to perpetrators are predominantly female. Feel free to imagine

the information using varied gender pronouns, such as he, ze or

s/he. |

| |

ABUSE IS NOT S/M AND S/M IS NOT ABUSE

Whether you are topping, or bottoming, or both, these are some questions to ask yourself:

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright

© 2003 Northwest Network.All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||

"Many cultures hold that men have the right to control their wives' behavior and that women who challenge that right—even by asking for household money or by expressing the needs of the children—may be punished. In countries as different as Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe, studies find that violence is frequently viewed as physical chastisement—the husband's right to “correct” an erring wife (10, 39, 94, 189, 204, 233, 303, 341, 407, 488). As one husband said in a focus-group discussion in Tamil Nadu, India, “If it is a great mistake, then the husband is justified in beating his wife. Why not? A cow will not be obedient without beatings” (233)." (Ending violence against women, a report from the Center for Communications Programs, Johns Hopkins University at http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11chap2_2.shtml#top)

From the University of Michigan Health System Tools & Resources: Culture and Domestic Violence

Help Minority Battered Women Seek Assistance!

Cultural Barriers for African American Victims of Domestic Violence

Internal Barriers:

External Barriers:

Sources:

Campbell, DW. "Nursing Care of African-American Battered Women: Afrocentric

Perspectives." AWHONN's Clinical Issues in Nursing. 4(3): 407-415.

1993.

Robinson, MS. "Battered Women: An African American Perspective."

The ABNF Journal. pp. 81-84. 1991.

Cultural Barriers for Asian Victims of Domestic Violence

Internal Barriers:

External Barriers:

Source:

Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence

Cultural Barriers for Latino Victims of Domestic Violence

Internal Barriers:

External

Barriers:

Source: "Bauer

HM, et.al. "Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian Immigrant

Women." Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. Vol

(1) 11. pp. 33-44. 2000.

AYUDA Family Violence and Prevention Fund

Culture and Domestic Violence: A Select Bibliography

Adams, DL. (Ed.) Health Issues for Women of Color: A Cultural Diversity Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995.

Berenson AB, Stiglich NJ, et al. "Drug Abuse and other Risk Factors for Physical Abuse in Pregnancy among White non-Hispanic, Black, and Hispanic Women." American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 164: pp. 1491-1499. 1991.

Burns, MC (ed) The Speaking Profits US: Violence in the Lives of Women of Color. Seattle, WA: Center for the Prevention of Sexual and Domestic Violence.1986.

Campbell JC, Campbell DW. "Cultural Competence in the Care of Abused Women." Journal of Nurse Midwifery. 41(6): pp. 457-462.1996.

Campbell, DW. "Nursing Care of African-American Battered Women: Afrocentric Perspectives." AWHONN's Clinical Issues. 4 (3): pp. 407-415. 1993.

Denis RE, Key LJ, et al. "Addressing Domestic Violence in the African American Community." Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 6(2): pp. 284-293.1995.

Galanti, GA. Caring for Patients of Different Cultures. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

Huisman, KA. "Wife Battering in Asian American Communities: Identifying the Service Needs of an Overlooked Segment of the US Population." Violence Against Women. 2(3) pp. 260-283. 1996.

Panigua, F. Assessing and Treating Culturally Diverse Clients. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. 1994.

Richie, BE. Understanding Family Violence Within US Refugee Communities: A Training Manual. Washington, DC: Refugee Women In Development, Inc, 1988.

Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ. "Partner Violence, Social Support, and Distress Among Inner-City African American Women." American Journal of Community Psychology. 28(1) pp. 127-143. 2000.

Sorenson SB. "Violence Against Women: Examining ethnic differences and commonalties." Evaluation Review. 20(3) p. 123. 1996.

Volpp L, Main L. Working with Battered Immigrant Women: A Handbook to Make Services Accessible. San Francisco, CA: Family Violence Prevention Fund, 1995.

White, EC. Chain Chain Change: For Black Women in Abusive Relationships. Seattle. WA: Seal Press. 1994.

http://www.med.umich.edu/multicultural/ccp/cdv.htm

Despite the obstacles, many women eventually do leave violent

partners—even if after many years, once the children are grown (129,

227). In Le'n, Nicaragua, for example, the likelihood that an abused

woman will eventually leave her abuser is 70%. The median time that women

spend in a violent relationship is five years. Younger women are more

likely to leave sooner (131).

Studies suggest a consistent set of factors that propel women

to leave an abusive relationship: The

violence gets more severe and triggers a realization that “he”

is not going to change, or the violence begins to take a toll on the children.

Women also cite emotional and logistical support from family or friends

as pivotal in their decisions to leave (52, 62, 65, 69,

202, 413).

Leaving an abusive relationship is a process. The process often

includes periods of denial, self-blame, and endurance before women come

to recognize the abuse as a pattern and to identify with other women in

the same situation. This is the beginning of disengagement and recovery.

Most women leave and return several times before they finally leave once

and for all (264).

Regrettably, leaving does not necessarily

guarantee a woman's safety. Violence sometimes continues and may even

escalate after a woman leaves her partner (227). In fact, a woman's risk

of being murdered is greatest immediately after separation (60).http://www.infoforhealth.org/pr/l11/l11chap2_3.shtml

Since Congress enacted the Violence Against Women Act as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, HHS has significantly expanded its efforts. HHS quadrupled resources for battered women's programs and shelters, created a national toll-free domestic violence hotline (1-800-799-SAFE), and expanded efforts to raise awareness of domestic violence in the workplace and among health care providers. In fiscal year 2001, Congress appropriated $244.5 million for HHS programs to prevent violence against women, including $2.2 million for the National Domestic Violence Hotline. President Bush's fiscal year 2002 budget increases that commitment to $251 million.

BACKGROUND

The landmark Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), administered by HHS and the Department of Justice (DOJ), provided funding to hire more prosecutors and improve domestic violence training among prosecutors, police officers, and health and social services professionals. It also provided for more shelters, counseling services and research into causes of violence and effective community campaigns to reduce violence against women.

The VAWA set new federal penalties for those who cross state lines to continue abuse of a spouse or partner, making interstate domestic abuse and harassment a federal offense. It also requires states to honor protective orders issued in other states and gives victims the right to mandatory restitution and the right to address the court at the time of sentencing.

In 1995, HHS and DOJ created the National Advisory Council on Violence Against Women, consisting of experts from law enforcement, media, business, sports, health and social services, and victim advocacy. The council works with both the public and private sectors to promote greater awareness about the problem of violence against women and its victims, to help devise solutions, and to advise the federal government on these issues. In October 2000, the council released an "Agenda for the Nation on Violence Against Women," which outlines recommendations for future efforts to build on the early successes of the VAWA.

In October 2000, Congress reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act programs as part of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.

HHS PROGRAMS UNDER VAWA

Grants for battered women's shelters. The VAWA significantly expanded HHS funding for battered women's shelters. Since the law was passed, HHS' grants for these programs more than quadrupled from $27.6 million in fiscal year 1994 to $116.9 million in fiscal year 2001. The reauthorization legislation enacted in 2000 increased the minimum grant amount for each state from $400,000 to $600,000. These resources also support related services, such as community outreach and prevention, children's counseling, and linkage to child protection services.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline. In 1996, HHS launched the National Domestic Violence Hotline, a 24-hour, toll-free service that provides crisis assistance and local shelter referrals for callers across the country. Since then, the hotline has responded to more than 500,000 calls, mostly from individuals who have never before reached out for assistance. HHS funds the hotline through a grant to the Texas Council on Family Violence. The hotline number is 1-800-799-SAFE, and the TDD line for the hearing impaired is 1-800-787-3224.

Grants to reduce sexual assault. HHS provides grants to states for rape prevention and education programs conducted by rape crisis centers or similar nongovernmental, nonprofit entities. The funds support educational seminars, the operation of hotlines, training programs and other activities to increase awareness of and help prevent sexual assault, including programs targeted to students. HHS funding for the program in fiscal year 2001 is $44.1 million. In addition, $7 million from the Preventive Health and Health Services Block Grant is earmarked for rape prevention programs.

Coordinated community responses. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) works to build new community programs aimed at preventing intimate partner violence and strengthening existing community intervention and prevention programs. The CDC is currently funding a total of 10 projects and received $5.9 million to fund these efforts in fiscal year 2001. CDC has also conducted the National Violence Against Women survey and completed a study on the cost of violence against women. CDC funds numerous cooperative agreements with state health departments to improve understanding of the issue.

Outreach to runaway, homeless youth. HHS funds a program to provide street-based outreach and education, including treatment, counseling and provision of information and referrals to runaways, homeless and street youth who have been subjected to or are at risk of sexual abuse. The program was appropriated at $15 million for fiscal year 2001.

OTHER HHS INITIATIVES

National resource centers. The Administration for Children and Families (ACF) funds a network of five national resource centers that provide information, technical assistance and research findings related to domestic violence. The network includes the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (800-537-2238), the Battered Women's Justice Project (800-903-0111), the Resource Center on Child Custody and Protection (800-527-3223), the Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence (888-792-2873), and the Sacred Circle Center on Violence Against Native Women (605-341-2050). The CDC funds the National Electronic Violence Against Women Resource Network (VAWnet) and the National Sexual Assault Resource Center (http://www.nsvrc.org). The VAWnet is an online resource for advocates working to end domestic violence, sexual assault and other violence in the lives of women and their children. The electronic library is available at http://www.VAWnet.org.

Child welfare grants. HHS has funded 26 grants over three years to local programs to stimulate collaboration between child welfare agencies and domestic violence providers. These projects train child welfare staff to identify and respond appropriately to instances of domestic violence in their caseloads. In addition, HHS has awarded 13 training stipends to schools of social work to develop curricula and train social workers in family violence.

Welfare Reform and Family Violence. In 1996, Congress enacted the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunities Reconciliation Act, which included provisions to help welfare recipients who are victims of domestic violence move successfully into work. Specifically, the provisions give states the option to screen welfare recipients for domestic abuse; refer them to counseling and supportive services; and temporarily waive any program requirements that would prevent recipients from escaping violence or would unfairly penalize them.

Guidelines on effective intervention. Supported by HHS and DOJ funding, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges developed a best practice guidelines for handling child protection cases involving domestic violence. The group published "Effective Intervention in Domestic Violence and Child Maltreatment Cases: Guidelines for Policy and Practice" in 1999. In 2000, following a competitive process, six sites were selected to demonstrate the effectiveness of community collaborations in implementing the report's recommendations.

Mental health, substance abuse and violence. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) supports several programs addressing substance abuse and mental health issues among victims of violence. These efforts include a five-year study designed to develop effective integrated service programs for women and their children affected by violence and co-occurring mental and addictive disorders. The program has yielded several comprehensive curricula to train substance abuse, mental health and other health and human services professionals on working with women victims of violence. Another multi-year SAMHSA grant program focuses on the connection among domestic violence, mental illness, substance abuse and homelessness among women and their children by assessing the effectiveness of time-limited intensive treatment, housing, support and family preservation services to homeless mothers and their dependent children.

Research initiatives. In 2000, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) awarded $5.5 million to fund four comparative studies examining the effectiveness of intervention programs offered in health care settings. AHRQ and the nonprofit Family Violence Prevention Fund also jointly sponsor a Scholar in Residence, who is developing better ways to assess health system interventions. In addition, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) funds a number of research studies focusing on the mental health consequences of violence, treatments for the traumatic consequences of violence, and factors that influence the initiation of physically aggressive behavior in intimate relationships. These studies have significant implications for preventing and reducing the mental health consequences of domestic violence.

Related programs. HHS agencies run and support a wide range of programs that provide services, information and other resources to address violence against women as part of broader program goals. For example, the Administration on Aging (AoA) funds elder abuse prevention programs in all 50 states that focus on the prevention of elder abuse, neglect and exploitation - including domestic violence. In addition, many HHS programs aim to strengthen families, prevent the abuse of women and children, and help families provide a healthy and safe environment for children. These programs include the Promoting Safe and Stable Families program and Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act grants.

Where

can I get help if I am being abused?

The National Domestic Violence Hotline, available 24 hours a day, 7 days

a week, provides services in English and Spanish. If you or someone you

know is being abused, contact the Hotline at (800) 799-7233. The Rape,

Abuse and Incest National Network also operates a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week

hotline for victims of sexual assault. The Network automatically connects

callers to a rape crisis center in their community where they can find

counseling and support. You can reach the Network at (800) 656-4673.

Back to top

Intimate Partner Violence

Like

all violence, intimate partner violence perpetration is a learned behavior

that can be changed or prevented.

Safety Tips for You and Your Family

If

you are the victim of intimate partner violence, do not blame yourself.

Talk with people you trust and seek services. Contact your local battered

women’s shelter or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at

800-799-SAFE (7233), 800-787-3224 TDD, or www.ndvh.org/.

They can provide you with helpful information and advice.

If

you are or think you may become a perpetrator of intimate partner

violence contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-SAFE

(7233), 800-787-3224 (TDD), or www.ndvh.org/.

They can provide you with helpful contact information.

Recognize

early warning signs for physical violence such as a partner's extreme

jealousy, controlling behavior, verbal threats, history of violent

tendencies or abusing others, and verbal or emotional abuse.

Know

what services are available for victims and perpetrators of intimate

partner violence and their children in case you or a friend should

need help.

Learn more about intimate partner violence. Information is available in libraries, from local and national domestic violence organizations, and through the Internet. The more you know about intimate partner violence, the easier it will be to recognize it and help friends who may be victims or perpetrators.

In Your Community

Support increased access to services for victims and perpetrators of intimate partner violence as well as for their children.

Coordinate community initiatives to strengthen safety networks for women who experience violence.

Increase public awareness to help decrease and prevent intimate partner violence.

CDC Resources

Preventing

intimate partner violence requires the support and contribution of a variety

of partners.

National Sexual Violence Resource Center

www.nsvrc.org

877-739-3895

A clearinghouse of information, resources, and research, related to all

aspects of sexual violence. Activities include collecting, reviewing,

cataloging, and disseminating information related to sexual violence;

coordinating efforts with other organizations and projects; providing

technical assistance and customized information packets on specific topics;

and maintaining a website with current information including upcoming

conferences, funding opportunities, job announcements, research, special

events, links to state and territory coalitions, and other resources.

The NSVRC also produces a biannual newsletter, The Resource; recommends

speakers for conferences; coordinates national sexual assault awareness

activities; and identifies emerging policy issues and research needs.

The NSVRC serves coalitions, local rape crisis centers, government and

tribal entities, colleges and universities, service providers, researchers,

allied organizations, policy-makers, and the general public.

National Violence Against Women Prevention Research Center

www.vawprevention.org

843-792-2945

Helps prevent violence against women by advancing knowledge about prevention

research and fostering collaboration among advocates, practitioners, policy

makers, and researchers. Over the next five years, the NVAWPRC and its

partners at CDC will be involved in a number of activities to accomplish

this mission. The NVAWPRC serves as a clearinghouse for prevention strategies

and keeps researchers and practitioners aware of training opportunities,

policy decisions, and recent research findings. The NVAWPRC website also

offers the latest research on violence against women as a resource to

everyone involved in the field of violence prevention so they can better

do their work.

Violence Against Women Electronic Network (VAWnet)

www.vawnet.org

Provides support for the development, implementation, and maintenance

of effective violence against women intervention and prevention efforts

at the national, state, and local levels through electronic communication

and information dissemination. VAWnet participants, including state domestic

violence and sexual assault coalitions, allied organizations, and individuals,

have access to online database resources. Network members are able to

engage in information sharing, problem-solving, and issue analysis via

electronic mail and a series of issue-specific forums facilitated by nationally

recognized experts in the field of violence against women. VAWnet also

operates an extensive searchable electronic library available to the general

public, providing links to external sources; an “In the News”

section; and access to articles and audio and video resources focused

on intimate partner and sexual violence and related issues.

Other Resources

The

materials presented herein are for information purposes only. We have

not screened each individual or organization that appears on this site

or that is electronically linked to this site. The appearance of an individual

or organization on this site is not intended as an endorsement. We urge

all users of this site to conduct their own investigations of the products

or services identified herein.

This list is not comprehensive but presents some of the major national

violence against women resources and national organizations addressing

violence against women.

If you are experiencing an emergency, call 911 or your local emergency

number immediately.

American Bar Association

Commission on Domestic Violence

phone: 202.662.1737/1744

fax: 202.662.1594

www.abanet.org/domviol/home.html

The members of the Commission help resolve problems in family law, criminal

law, victims' and individuals' rights, judicial administration, tort and

civil rights litigation, and immigration law. Representatives of other

professional organizations serve on the Commission to help develop a national

domestic violence agenda as well as to enhance existing policies and solutions

in the constantly changing fields of state and federal domestic violence

law.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

409 12th Street SW

Washington, DC 20024-2188

phone: 202.638.5577

www.acog.org

ACOG is the nation's leading group of professional providing health care

for women. ACOG is dedicated to the advancement of women's health through

education, advocacy, practice, and research.

American Institute on Domestic Violence

2116 Rover Drive

Lake Havasu City, AZ 86403

phone: 928.453.9015

fax: 775.522.9120

www.aidv-usa.com

The American Institute on Domestic Violence offers on-site workshops and

conference presentations addressing the corporate cost of domestic violence

in the workplace.

Asian and Pacific Islander Institute on Domestic Violence

942 Market Street, 2nd Floor

San Francisco, CA 94102

phone: 425.954.9964

fax: 415.954.9999

www.apiafh.org/

The Asian and Pacific Islander Institute on Domestic Violence is a national

network that works to raise awareness in Asian & Pacific Islander

communities about domestic violence; expand leadership and expertise within

Asian & Pacific Islander communities about prevention, intervention,

advocacy and research; and promote culturally relevant programming, research,

and advocacy by identifying promising practices.

Battered Women's Justice Project

phone: 800-903-0111

fax: 218-722-0779

http://www.bwjp.org/

The Battered Women’s Justice Project consists of three sections,

criminal justice, civil justice and the defense of battered women charged

with crimes.

Communities Against Violence Network

www.cavnet2.org

Communities Against Violence Network (CAVNET) provides an interactive

online database of information; an international network of professionals;

and real-time voice conferencing with professionals and survivors, from

all over the world, using the Internet. CAVNET seeks to address violence

against women, youth violence, and crimes against people with disabilities

Corporate Alliance to End Partner Violence

2416 E. Washington Street, Suite E Bloomington, IL 61704-4472

phone: 309.664.0667

fax: 309.664.0747

www.caepv.org

The Corporate Alliance to End Partner Violence (CAEPV) is a national non-profit

alliance of corporations and businesses throughout the U.S. and Canada,

united to educate and aid in the prevention of partner violence. CAEPV

provides technical assistance and materials to help corporations and businesses

address domestic violence in their workplaces.

The Family Violence Prevention Fund

383 Rhode Island Street, Suite 304

San Francisco, CA 94103-5133

phone: 415.252.8900

fax: 415.252.8991

www.endabuse.org

The Family Violence Prevention Fund is a national non-profit organization

most noted for it’s national public education campaign “There’s

No Excuse for Domestic Violence.” The Fund also has a National Health

Initiative on Domestic Violence that works to train health care providers

throughout the nation to recognize signs of abuse and to intervene effectively

to help battered women. Hallmarks of this initiative include: the Ten-State

Pilot Health Care Response to Domestic Violence program working to develop

and implement state wide plans for a comprehensive health care system

response to domestic violence; and the FVPF's Health Resource Center on

Domestic Violence, which acts as the nation's clearinghouse for information

on the health care response to domestic violence. Other projects include

the Judicial Education Project, the Child Welfare Project, the National

Workplace Resource Center on Domestic Violence, and the Battered Immigrant

Women's Rights Project. Their Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence

Provides resource and training material, technical assistance, information

and referrals, and models for local, state and national health policymakers

to support those interested in developing a comprehensive health care

response.

The Institute on Domestic Violence in the African American Community

University of Minnesota/School of Social Work

290 Peters Hall

1404 Gortner Ave.

St. Paul, MN 55108-6142

phone: 877.643.8222

fax: 612.624.9201

www.dvinstitute.org

The Institute on Domestic Violence in the African American Community seeks

to create a community of African American scholars and practitioners working

in the area of violence in the African American community, further scholarship

in the area of African American violence, raise community consciousness

of the impact of violence in the African American community, inform public

policy, organize and facilitate local and national conferences and training

forums, and to identify community needs and recommend best practices.

Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse

School of Social Work, University of Minnesota 105 Peters Hall, 1404 Gortner

Avenue St. Paul, Minnesota 55108-6142

phone: 612.624.0721

fax: 612.625.4288

www.mincava.umn.edu

The Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse (MINCAVA) is an electronic

clearinghouse located in the School of Social Work of the University

of Minnesota with educational resources about all types of violence,

including higher education syllabi, published research, funding sources,

upcoming training events, individuals or organizations which serve as

resources, and searchable databases with over 700 training manuals, videos

and other education resources. MINCAVA is also part of a is a cooperative

project - the Violence Against Women Online Resources - between the Center

and the United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs,

Violence Against Women Office. This website

provides law, criminal justice, and social service professionals with

current information on interventions to stop violence against women.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence

P.O. Box 18749 Denver, CO 80218 phone: 303.839.1852 fax: 303.831.9251

www.ncadv.org

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV) is a membership

organization of domestic violence coalitions and service programs. NCADV

provides training, technical assistance, legislative and policy advocacy,

promotional and educational materials and products on domestic violence;

coordinates a national collaborative effort to assist battered women in

removing the physical scars of abuse; and works to raise awareness about

domestic violence.

National Domestic Violence Hotline

PO Box 161810

Austin, TX 78716

phone hotline: 1.800.779.SAFE (7233)

tty:1.800.787.3224

administrative: 512.453.8117

fax: 512.453.8541

www.ndvh.org

The National Domestic Violence Hotline connects individuals to help in

their area using a nationwide database that includes detailed information

on domestic violence shelters, other emergency shelters, legal advocacy

and assistance programs, and social service programs. Help is available

in English or Spanish, 24 hours a day, seven days each week. Interpreters

are available to translate an additional 139 languages.

National Latino Alliance for the Elimination of Domestic Violence

P.O. Box 322086 Ft. Washington Station New York, NY 10032

phone: 646-672-1404 or 1-800-342-9908 fax: 1-800-216-2404

www.DVAlianza.org

The National Latino Alliance for the Elimination of Domestic Violence

(the Alianza) is a group of nationally recognized Latina and Latino advocates,

community activists, practitioners, researchers, and survivors of domestic

violence working together to promote understanding, sustain dialogue,

and generate solutions to move toward the elimination of domestic violence

affecting Latino communities, with an understanding of the sacredness

of all relations and communities. Support from ACF/DHHS has allowed the

Alianza to establish El Centro: National Latino Research Center on Domestic

Violence and the Alianza Training and Technical Assistance (T/TA) Division.

National Network on Behalf of Battered Immigrant Women

http://www.endabuse.org/programs/immigrant/

The National Network on Behalf of Battered Immigrant Women was co-founded

in 1994 by the Family Violence Prevention Fund, AYUDA, NOW Legal Defense

and Education Fund and the National Immigration Project of the National

Lawyers Guild to nationally coordinate advocacy efforts aimed at removing

the barriers battered immigrant and children face when they attempt to

leave abusive relationships. Each organization provides leadership in

their area of expertise.

National Network to End Domestic Violence

660 Pennsylvania Ave. SE, Suite 303

Washington, DC 20003

phone: 202.543.5566

www.nnedv.org

The National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) is a membership

and advocacy organization of state domestic violence coalitions. NNEDV

provides legislative and policy advocacy on behalf of the state domestic

violence coalitions and, through the National Network to End Domestic

Violence Fund, provides training, technical assistance and funds to domestic

violence advocates.

National Resource Center on Domestic Violence

6400 Flank Drive, Suite 1300

Harrisburg, PA 17112-2778

phone: 800-537-2238

tty: 800-553-2508

fax: 717-545-9456

www.vawnet.org

The National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRC) provides comprehensive

information and resources, policy development and technical assistance

designed to enhance community response to and prevention of domestic violence.

There are 40 NRC publications, as well as NRC project descriptions and

project publication lists available via VAWnet. These NRC projects include

the Building Comprehensive Solutions to Domestic Violence Initiative,

the Public Education Technical Assistance Project, and VAWnet.

National Training Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence

2300 Pasadena Drive

Austin, TX 78757

phone: 512.407.9020

fax: 512.407.9022

www.ntcdsv.org

The National Training Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence develops

and provides innovative training and consultation, influences policy and

promotes collaboration and diversity in working to end domestic and sexual

violence. NTCDV has a staff of nationally known trainers and sponsor national

and regional conferences.

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN)

www.rainn.org

hotline: 800.656.HOPE

RAINN is the country’s only national rape hotline. RAINN works as

a call-routing system. When an individual calls RAINN a computer reads

the area code and first three digits of their phone number and routes

the call to the nearest member rape crisis center.

Sacred Circle: Native Resource Center to End Violence Against Native Women

PO Box 638

Kyle, SD 57752

phone: 877.733.7623 (red-road)

fax: 605.341.2472

www.sacred-circle.com

Provides technical assistance, policy development, training institutes,

and resource information regarding domestic violence and sexual assault

to develop coordinated agency responses in American Indian/ Alaska Native

tribal communities.

The Stalking Resource Center

c/o National Center for Victims of Crime

2000 M Street NW, Suite 480

Washington, DC 20036

phone: 202.467.8700 fax: 202.467.8701

www.ncvc.org

The Stalking Resource Center is a project of the National Center for Victims

of Crime, funded through the Violence Against Women Office, U.S. Department

of Justice. The Stalking Resource Center has established a clearinghouse

of information and resources to inform and support local, multi disciplinary

stalking response programs nationwide; developed a national peer-to-peer

exchange program to provide targeted, on-site problem-solving assistance

to VAWO Arrest grantee jurisdictions; and organized a nationwide network

of local practitioners representing VAWO grantee jurisdictions to support

their multi disciplinary approaches to stalking.

Federal Agencies

Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

Division of Violence Prevention

4770 Buford Highway, NE MS K-60

Atlanta, GA 30341

Fax: 770-488-4349

www.cdc.gov/injury

The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) guides national

efforts to reduce the incidence, severity, and adverse outcomes of intentional

and unintentional injuries in the United States. As the lead federal agency

for injury prevention, NCIPC works closely with other federal agencies

and national, state, and local organizations to reduce injury, disability,

and premature death. NCIPC’s priority areas for violence prevention

are: child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, suicide

and youth violence. Project and activities focus on primary prevention

of violence through a public health approach.

Department of Health and Human Services,

The Office on Women’s Health,

National Women’s Health Information Center (NWHIC)

Office on Women's Health

Department of Health and Human Services

200 Independence Avenue, SW

Room 730B Washington, DC 20201

Phone: 202-690-7650

Fax: 202-205-2631

www.4woman.gov/

The National Women's Health Information Center (NWHIC) is the Office on

Women's Health's clearinghouse for women's health information. The NWHIC

provides a gateway to the vast array of Federal and other women's health

information resources. This site provides links to a wide variety of women's

health-related material developed by the Department of Health and Human

Services, other Federal agencies, and private sector resources.

U.

S. Department of Justice, Office for Victims of Crime

Office for Victims of Crime Resource Center

National Criminal Justice Reference Service

P.O. Box 6000